Ch'an Dao Links:

|

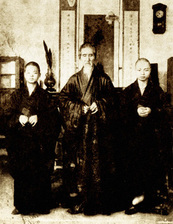

Xu Yun (1840-1959) Present Awareness

Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) was one of the last great Ch’an masters of China. There are others of course, and each has contributed in his or her own unique fashion – to the preservation of the Chinese Buddhist Schoolknown as ‘Ch’an’. Master Xu Yun lived much of his very long life during the 19th century, before entering a 20th century that would see the ancient civilisation of China ripped apart, and its people suffer probably more than in any other time in its history. This is a remarkable statement to make when the length of Chinese history is considered, together with the many and bloody wars that signified the end and the beginning of different dynasties. This culture formed around an official hierarchy and a very deep sense of martial prowess. The hierarchical nature of traditional Chinese society – believed to have been endorsed by the great sage Confucius –was really an attempt to retain social order by defining clearly, differing social ranks and the responsibilities such an ascribed rank entailed. When working at its best, the system allowed for those without experience to follow those who had experience – thus ensuring the more mature were always in control of the less knowledgeable. Eventually, of course, those who followed would learn to be wise and assume the responsibility of teaching, participating in a cycle of continuous self-improvement. The theory was that today’s students would be tomorrow’s teachers, just as today’s children would be tomorrow’s parent, etc. The patriarchal nature of Chinese society ensured that virtually every emperor was a man, to whom the entirety of China looked-up to and obeyed without question, and that the every ordinary family living in China was a replication of the imperial court, with the wife and children obeying the father as if he were the emperor himself. The five relationships of China – the ruler to rule, father to son, husband to wife, elder brother to younger brother, and friend to friend – were considered the very foundational order that Chinese society was based upon, and the defining quality that separated a superior Chinese culture from that of the inferior ‘foreign’ and barbaric one. Duty and filial respect acted as the social glue that held it all together. Within traditional Chinese society the social order is not necessarily that which is imposed from the outside, but is rather internally created within the mind of every child from an early age, so that the outer culture is merely an externalised inner preference. The child grows-up knowing only the five relationships, and this forms an important psychological structure within the mind of the adult individual. In this regard, tradition Chinese society does, and can not, recognise the notion of the ‘individual’ in the Western sense of the term. Within Chinese society every single person – without exception – is part of the social fabric of duty bound interaction. Freedom of expression is not allowed because it does not ‘fit-in’ to any of the specified five relationships. Freedom to express anything that is not strictly predictable is defined as an act of social chaos. That is not to say that things can not change, but that the process of change (and by association the realisation of innovation) happens in a very controlled manner, with the emphasis always being toward the preservation of the present status quo. This does create a stable outer climate when it is functioning correctly, but one that is designed never to have its underlying notions questioned in anyway. What change there is, is allowed because it is viewed as conforming to a set of very stringent guiding principles. Thousands of years of this kind of social organising did lead to a myriad of technical developments – often hundreds of years a head of Western development. This society is Considered Confucian in nature, and indeed the study of the Confucian Classics is believed to be the only education worth pursuing, as the wisdom of the ancient sages is imbued in the student’s mind. However, even a cursory examination of the classical Confucian texts will reveal a Confucius concerned with gentlemanly behaviour and duty – this is true – but also a deep humanity set upon self development that is often very subtle and of a far greater reach than the mere interpretation of social conformity that later governments imposed upon his teachings.

Often it has been the case that to be spiritual in China is to condemn oneself to a life lonely wondering within the hills. In reality, an ‘other worldly’ aspiration that is not catered for through a state defined Confucian ritual results in the aspirant having to leave the world of everyday life and seek out solitude away from judging eyes. This had already been the case for Daoism with many of its sages living on the top of mountains –indeed, so common was this occurrence that it came to represent the concept of what it was to be an ‘immortal’. It is ironic to consider that the sages that Confucius respected were very much of the Daoist mould, and that the obsession of giving birth to boys within marriage is apparently against the saying of Confucius which declares that a true sage has no descendents. The arrival of Buddhism from Indiaat around 100CE was problematic. The Indian notion that leaving home and giving up social responsibilities was ‘spiritual’ was asymmetrically opposed to the established Chinese tradition of the family and clan being the facilitator of religious ritual. Each family within a name clan, and the clan itself would have temples and altars set-up for the various religious rituals that occurred throughout the year. Religion of this nature is set to the calendar, decreed by the emperor, and carried-out as a communal activity. Leaving the social network is viewed as leaving the civilised world which is sustained through the correct (and timely) performance of ritual which regulates the flow of ‘qi’ (vital force) throughout Chinese society. The root of this ritual is the veneration of the ancestors who dwell in the heavenly realm. Correct behaviour toward them ensures that the qi flows without blockage and that the crops will ripen, animals will stay healthy and children will be born. Buddhism was tolerated however, despite some historical ups and downs, but leaving home to become a monk has always been a difficult affair. It still was in 1858 when master Xu Yun decided to leave home and pursue the Buddhist monastic path. As his father was a government official, Xu Yun was expected to follow in his footsteps, get married and produce a son to keep the family name of Xiao going. Even though he had expressed spiritual inclinations to his father, his father would not give permission for him to leave. Instead his father arranged for a Daoist teacher to come to the family home and teach Xu Yun internal and external qigong – or ‘energy work’. Considering how many fathers from this era would probably have merely decreed a marriage and not discussed the matter any further, this action may be viewed as some thing of a compromise. However, Xu Yun was not satisfied with the Daoist teachings as they differed from the Buddhist teachings of Dharma. As he could not get his father’s permission, Xu Yun decided to leave home without it – a shocking decision for the time – and go into the hills to seek out the Buddhist masters. This he did, and although his motivation was to follow the Buddhist path, by heading into the hills he was following the old tradition of the ancient sages which amounted to the experience of a kind of social death, whereby the aspirant had no further choice left but to pursue the lonely path to the very end. Reading the autobiography of master Xu Yun, every occurrence and happening – good or bad – is recorded with a matter of fact attitude. In reality, much of what it describes could not have been like that at all. This is not to imply that the autobiography is dishonest – far from it – but that in his unassuming manner Xu Yun always played down his own suffering. Often the reader has to rely upon the added notes of Xu Yun’s editor – Cen Xue-Lu – to gain vital background information to important events. Xu Yun would often say something like 'a misfortune befell me’, and leave it at that. This approach of spiritual self-sufficiency is the product of living in the wilderness outside of a society that eulogises the community over the individual. Generally speaking no help was forthcoming outside of the Buddhist groups and establishments, indeed, many homeless monks often relied upon their families to support them with food and clothing, as Buddhist monks were not allowed to beg in China. It is a curious paradox that involves the experience of social rejection to pursue an ancient path to sagehood, with occasional support from relative that are supposed to have been left behind. Living in the wilderness was a potentially dangerous activity. Poor weather, lack of clothing and shelter, attacks from bandits and wild animals all conspired to cause, illness, injury or death. Master Xu Yun spent many years in isolated meditation, but he believed fully that a calm and expansive mind can over-come all threats of danger by emanating waves of psychic qi into the environment and inwardly transforming all that it came into contact with. Wild animals would divert their hunting away from the spot of meditation and potentially violent people would not feel the urge to cause trouble. When bad weather struck, master Xu Yun would enter deep meditation (Samadhi), and regardless of his outer environment, his body would be preserved and safe, regardless of the length of time in that state. Master Xu Yun lived his time on this planet through his physical body, but from a very young age he did not feel that he was his body. His answer was to pursue the Buddhist path – and eventually the Ch’an method – to become mindful and clear about his real nature that was not simply the physical body, its senses and desires. He did not meditate in purpose built meditation centres common in the contemporary West, but rather confronted his own deluded mind face to face. For Xu Yun the physical body was not something that needed to be made ‘comfortable’, as this process itself is an act of the very delusion that he was striving to over-come. This kind of commitment was complete and thorough – the physical body and the material world it inhabited – were the problem set before the mind’s inner eye. The Buddha, thousands of years ago found the truth he sought and developed a path for others to follow. Today there is a very definite trend within Buddhism of intellectual understanding taking the place of practice and actual realisation. It is as if by the act of formulating an understanding about what enlightenment might be, enlightenment itself has been attained. Of course, this is an absurdity of delusion that imagines itself as higher knowledge, rather than the shackle it actually is. Unless the aspirant commits himself to an ardent path of meditation, no realisation will occur. Intellectualism, regardless of its refinement, is simply more delusion. Master Xu Yun, through his example of passing many years meditating in the wilderness is setting an eternal example of the kind of practice intensity that is required if the deluded mind is to be transcended. This is not an easy task. In the Tang Dynasty Ch’an literature examples abound of enlightenment occurring after a short dialogue with a master, or after some kind of demonstrative action, such as a slap, a kick or a shout. For the effectiveness of the Ch’an method this is an important observation. When Xu Yun was travelling through the Chinese hills in his youth, he did not come across any masters of this calibre and so had to rely upon meditative practice. This is not an error, or an inferior practice. It must be borne in mind that many of the apparently spontaneous acts of enlightenment happened in an instant; this is true, but usually after many years of meditative experience. It is a general belief within Ch’an circles that modern living creates a layer of delusion within the mind that is particularly dense and difficult to break through. Therefore cases of spontaneous enlightenment, although not impossible are nevertheless a rare occurrence. Even the gongan – the recorded dialogue between an enlightened student and a Ch’an master – is often held in the mind as a meditative aid within certain lineages. That is to say that the record of a free-flowing enlightened exchange is converted from its spontaneous ‘freeing’ function, to that of a potentially long term meditative method whereby the dialogue is imagined within the mind with a certain intensity that is designed to draw all thoughts into ‘its’ structure, and therefore eventually free the mind by removing the obscuring layer, thus revealing the Mind Ground within. This kind of usage applies the gong-an as a method of thought absorption, whereas originally the very same dialogue (comprising the gong-an) was representative of a penetrating insight that was cutting through a student’s mind layer of obscuring delusion and revealing the Mind Ground immediately, without recourse to method or technique. Eventually, this re-application of the gong-an was refined further into the hua tou – an ingenious device designed to reveal the essence of thought itself. Of course, if one thought is used to reveal the Mind Ground, all thoughts are necessarily uprooted and delusion is smashed. The hua tou internalises the enlightened exchange to a more subtle degree. A question that bests suits the ego being uprooted is given to the student – in reality the question itself is of no relevance – as long as the question begins with the word ‘who’? Whereas the original gong-an usage demonstrates a non-specific penetrative technique of instantaneous ‘turning about’ within the mind, the gong-an as a meditative device seeks to draw all thoughts to its mental structure where they are dissolved in concentrative effort. The hua tou reduces all thoughts to ‘who?’, and through the power of enquiry implicit within the word, not only dissolves all thoughts, but carries the enquiry into the empty essence of the mind itself. Both the gong-an and hua tou methods are designed to be used by the aspirant independent of any other external assistance, regardless of whether a master is present or not. In many ways these innovative Ch’an methods are designed to achieve the same end as that of concentrating upon the breath found within early Buddhism. The main distinction is that the Ch’an methods contain an implicit driving force that is designed to push the concentrated awareness beyond the mere awareness of the object of meditation. The Ch’an method combines both tranquillity and insight meditation into one powerful practice. There are no levels as such, merely enlightenment and the lack of enlightenment, even though there may appear to be many expedient levels of development. The hua tou particularly aims to replicate the exact moment the enlightened master penetrates the previously deluded mind of the student – thus instantaneously wiping out all delusions and revealing the Mind Ground. The interesting thing about this is that the student is effectively enlightening himself. After the initial opening of the mind, master Xu Yun teaches that a further period of meditation is required to wipe out all psychological habits. A ‘stilled’ mind still has the potential to experience klesa or impurities as it is not yet fully realised. Xu Yun likens this to a jar of water containing dirt – if the jar is left for a long time without being moved, the dirt will sink to the bottom and the water will appear clean. However, if the jar is picked up and shaken, the dirt re-appears through the water. When students are not instantaneously enlightened, but achieve lesser, but equally important states of development, further training is required to progress further. It is also true, however, that on occasion the Ch’an literature mentions students who are perfectly enlightened, but that still require a period of further training to clear-up residual mental habits. What is important is a central practice that firmly anchors the practitioner to the spiritual spot, so to speak, and allows for the penetration of the mind without error or doubt. Xu Yun does talk of a useful ‘doubt in the mind’ (yi-qing) that is spiritually positive. This kind of doubt does not allow the mind to settle for egoistic interpretations, or to development attachments to Dharma and insight. This type of doubt always knows that there is further development to be undertaken and is always watching for subtle delusions to develop, so that they can be cut-down without mercy. This is why a constructive doubt, coupled with an effective meditative method, can be ruthlessly applied on the spiritual path. When realisation occurs, its validity can be sought within the Ch’an literature, specific Mahayana Sutras and of course, and from qualified masters who might be monastic or lay, male or female. The Great Way knows no distinction. Master Xu Yun, over many decades experienced numerous enlightenment breakthroughs which he confirmed through scripture consultation and master consultation and dialogue. What is important is that false Ch’an is not indulged. Throughout virtually every age there have been various versions of so called heretical Ch’an taught by charlatans and fraudsters. These people and their methods exist even today and they lead many honest spiritual seekers astray. Teaching a false path to others to aggrandise the deluded ego leads only to terrible karma. The bad karma is magnified due to the fact that the Buddha’s teaching is being slandered and misrepresented, and that this effect is being magnified through the destroyed spiritual efforts of those who have been deliberately taken through the wrong path. Xu Yun demonstrated a brutally honest approach to self-cultivation and set an example of what is good and reliable Ch’an. The power of the mind as Xu Yun conceived, it was not an abstract idea that theorised about reality but never actually proved its theorisation. Instead, the mind in its entirety is the underlying reality to all phenomena, and it influences, guides and directs all physical experiences. Experiences come through the deluded mind as good, neutral and bad karmic experiences. By working upon the mind through meditation, not only is the fabric of the mind being transformed, but the sheer psychic power that is unleashed through meditation, is able to permeate the entirety of physical matter and change it for the better. This is the effect of waves of qi flowing outward in the ten directions. This is because everything exists within the mind and is inherently ‘empty’ of any permanent substance. The positive effect of meditation upon the environment however, regardless of its strength, is only a secondary manifestation and such an effect should not be given any undue attention. The physical body, regardless of its apparent state can be sustained spiritually through the meditative practice when a lifestyle within the wilderness is the only option. Illnesses and injuries can heal at a faster rate than normal when regular meditation is engaged within. Master Xu Yun was often ill, and occasionally hurt – this includes a terrible beating given to him by Red Guards when he was well over 100 hundred years. He demonstrated time and again the power of the human mind to achieve physical longevity and to endure often long term hardship. The level of qi development is often so strong in extensive meditators that they are often able to manifest unusual abilities and tremendous feats of strength. Xu Yun, of course, displayed this ability through the mundanity of his simple life on the road. He often refused to sleep in warm rooms and comfortable beds, but rather preferred being close to nature and the elements. In his life he was able to walk vast distances all over China, and this included travelling to foreign lands. The only transport he used was some form of boat to get across the seas – but only when necessary. He walked in all kinds of weather, including thick snow. Occasionally he would prostrate in prayer every third step, even when he was suffering from illness. Once, whilst travelling back from Burma he picked-up a very large and heavy boulder to prove to the labourers that were with him that they could carry the Buddha statue in their charge back to China. On the other hand, despite these obvious displays of spiritual power, Xu Yun always emphasised the act of meditation over the performance of miraculous feats. Indeed, when he visited the famous temple of Shaolin he made no mention of martial arts practice, but instead simply noted that Bodhidharma had once stayed there, whilst transmitting Ch’an Buddhism from India to China. Xu Yun was very well known from his travels within and outside of China. Although he never came to the West, he did travel to places such as India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Hong Kong, Tibet, Malaysia and even Thailand. Indeed, whilst in Thailand he was introduced to the king, who became his disciple. Much of Xu Yun’s popularity was due to his reputation as a pure follower of the Buddha’s path, and to his ability to effectively teach the Ch’an Dharma with compassion and wisdom. Although he did not come to the West, he did meet a number of Westerners, including the American Ananda Jennings (mentioned in his autobiography), and the British academic John Blofeld – both whom enquired about the Ch’an teachings. These meetings, no doubt, sparked an interested in Western Buddhist, and it is through this interest that he asked his lay student Charles Luk (1898-1978), to translate important key Chinese Buddhist texts into English so that Westerners might have a reliable resource for their meditative study. Not only this, but because of Xu Yun’s inspiration Charles Luk visited London as early as 1935, and when living in exile in Hong Kong due to the government of Mao Zedong on the Mainland, kept up an extensive written dialogue with Western Ch’an Buddhists, demonstrating the ancient Ch’an letter writing tradition prevalent in China. Such a tradition works upon the premise that a well chosen word or phrase can take a student beyond the reliance upon ‘words and phrases’. Charles Luk taught many people and one of his students from Great Britain - Richard Hunn (1949-2006) – was specifically asked by him to keep the English translations in print, and continue the Ch’an teaching. Today, the Richard Hunn Association for Ch’an Study (www.chan-forum.org) continues this tradition. Although Xu Yun did not physically travel to the West his influence has reached there through his students, with lineages in America, Britain, France, Bulgaria, Slovenia and many other places. His influence is demonstrative of the purity and strength of his enlightened mind, and the trust that he placed in particular individuals to take the Ch’an Dharma forward. Although he abandoned the world of family relations and had no descendents, the lineage that he perpetuates, takes forward the Shakya name of the Buddha, as a spiritual essence that spreads down through the ages. Today, as modern China recovers from the trauma of a destructive revolution with its pointless attacks upon tradition and religion, people such as master Xu Yun are being re-discovered and their teachings re-engaged. Their value as spiritual beings and cultural icons is now being recognised. Of course, other than his robe and one or two simple objects, Xu Yun did not wealth, family or social status and much of the time he led a physical existence that might be described as that of a wondering beggar. The outer physical body was just a vehicle to practice and spread the Dharma. His Chinese philosophical education was nothing short of first class as is evident through the content of his discourses delivered during Ch’an Weeks – that is times of extended meditation in a particular place attended by whoever wishes to meditate. Chinese history is replete with examples of extraordinarily gifted individuals that although lacking in material wealth have amassed an inner wealth through years of dedicated study – much like Confucius himself. Generally speaking, outer wealth is not necessarily a guarantee of knowledge, and even if a privileged upbringing does secure a certain education, it is doubtful that wisdom is a result. Wisdom is often the result of long suffering and self searching. In his teaching and lecturing Xu Yun often emphasised ‘good conduct’ as an important strand toward effective self-development. In this regard he spoke often and clearly about his belief in karma and the re-births experienced because of it. Not all experiences are directly related to volitional actions, but it is the volitional actions – that is patterns of behaviour formulated within the mind and manifest through actions in the physical world – that directly influence the kind of birth experienced, pulling disparate materials together to form a ‘life’. These conditions can be conducive to Dharmic practice or antagonistic to it. Obviously through pure intent and clean actions a good human re-birth is assured, together with the conditions that lead to the direct contact with the authentic Dharma. Deviation from this path leads to re-births in realms that do not allow the Dharma to be manifest or practiced – the human realm is unique in as much as deluded beings can escape from the suffering of their delusion whilst existing within. Greed, hatred and delusion, together with teaching the reality of materialism, the denying of karma and re-birth and distorting the Buddha’s teachings for selfish ends, leads invariably to non-human births, or to human births that entail negativity and a limited spiritual possibility. Feigning enlightenment and leading others into the dark tunnel of intensified delusion leads invariably to a state of enhanced suffering. This can be instantly changed if he need for reform is truly present. The escape from this mire is related to karma producing actions – change the actions and the inner and outer environment will be transformed for the better. Karmic fruit will manifest that are positive and bright drawing others to the glow of good Dharma cultivation. For Xu Yun, this was a crucial aspect of Ch’an training and a living reality – it was not an abstract theory. Just as the Buddha changed his life through meditation, so did master Xu Yun – following the principle of generating positive karma and acknowledging the living of numerous previous lives. Needless to say, without the acceptance of the idea that karma and re-birth are an integral and foundational aspect of Buddhist thinking, then the path of Ch’an can not be taken. Just ten years after Xu Yun left his body, his student Charles Luk, writing in his 1966 book entitled ‘The Surangama Sutra’, mentions the presence of materialists and blasphemers, particularly in the West who try to mislead other Westerners by expressing misinformed opinions disguised as freedom of speech, Buddhism is an art that must be mastered. As such it is comprised of many aspects. Ch’an, although often dispensing with the requirement for a formal Buddhist education, nevertheless involves the practice of a particular method which must be fully understood by the student, who should be guided by a living master or an authoritative text, or both. Many Ch’an practitioners, whilst following an extensive meditative path also learn about the sutras. Others abandon all learning until they have become clear about the Mind Ground. Whatever the case, neither type of student can say that they have understood the Dharma until they have personally experienced the Mind Ground and wiped out all notions of dualism and entered the all-embracing mind. Until that time, any one who has not experience this breakthrough can not speak with any authority about the Ch’an Dharma. Those not engaged in Buddhist practice at all, can not speak at all, and when they do they merely express the current superficial movements of their undeveloped mind. Master Xu Yun eventually experienced full enlightenment at aged 56 – in the year 1895-96. He dedicated his life to the practice and teaching of the Buddha Dharma, and the extent of his success can be measured from the fact that this monk (who was born in Fujian province and left home at around 19 years old), eventually inherited all of the five schools of Ch’an, breathing new life into an old tradition. His life served as the spiritual conduit for the modern world, and not just in China. In 1934 he had a number of visions of Hui Neng – the Sixth Patriarch – and after this event embarked upon a life time of temple and monastery restoration – an activity that he continued even after Mao Zedong’s government came to power, up until Xu Yun’s death in 1959. Despite being asked to stay in Hong Kong in his 110th year (1949-50) and not go back to the Mainland of China, Xu Yun responded by saying that he could not abandoned the people of China and that despite the change of government there was still much work to be done. The next decade, the last of Xu Yun’s very long life time, would see a time of great personal suffering the Xu Yun and for the people of China. Out of the pain of the material world the path of Ch’an emanates in to ten directions. Master Xu Yun is considered the right dharma eye for this generation. ©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2012. |