Ch'an Dao Links:

|

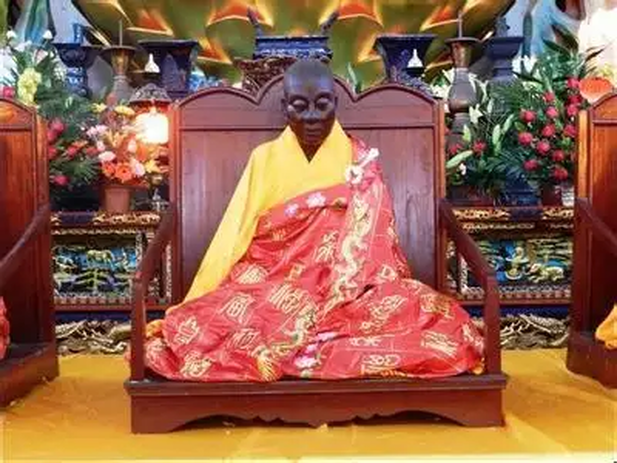

Charles Luk & Wong Mou Lam – and the Tale of Two Altar Sutras!Translator’s Note: As far as I am concerned, Master Hui Neng – the Sixth Patriarch of Ch’an Buddhism – was a real person. I know he once lived because he possessed a physical body that still exists and can be seen sat upright in eternal meditation by anyone who bothers to visits Nanhua (南華) Temple, situated in the town ‘Maba’ in Qujiang District, 25 km southeast of central Shaoguan, Guangdong province. This constitutes far more ‘evidence’ than is available for many other figures considered ‘historical’ in the Western tradition! Hui Neng was born in ‘Lingnan’ (南岭) - a geographical area of feudal China which was comprised of five mountain ranges – the Yuecheng (越城)-ling, Dupang (都庞)-ling, Mengzhu (萌渚)-ling, Qitian (骑田)-ling and Dayu (大庾 )-ling, The Suffix ‘岭’ (Ling) refers to a ‘mountain range’ - and therefore the name ‘Lingnan’ ((南岭) translates as ‘Mountain Ranges – South' - with ‘南’ (Nan) literally meaning ‘South’! In everyday usage, this designation refers to the barrier of five mountain ranges that exists across the ‘Southern’ boundary that defines the geographical limitation of the sovereignty of the Tang Dynasty! These mountain-ranges are distributed throughout eastern Guangxi, eastern Guangdong and run along the borders of Hunan and Jiangxi provinces. These five mountain-ranges present a psychological and physical ‘barrier’ that separates the ethnic Chinese from the non-Chinese peoples of the area. Historically, the concept of ‘Lingnan’ broadly corresponds to the entirety of Guangdong (including Hainan, Hong Kong, and Macau), Guangxi and eastern Yunnan, as well as parts of southwestern Fujian province. The ‘Yue’ (越) people are also known as the ‘jyut’ in the ‘Cantonese’ dialectic and this is how the term ‘Viet’ is arrived at. The ‘Yue’ is a collective name for numerous ancient non-Han tribes inhabiting Southern China and Northern Vietnam (living beyond the five mountain-ridges). These nomadic people existed through ‘hunting’ and ‘migrating’ from place to place and were distinguished from the Chinese by not conforming to the settled Confucian culture. As there were known to be many variants (or ‘tribes’) of the ‘Yue’ people, the prefix of ‘Bao’ (百) [which literally means ‘one-hundred’], was added – creating the term ‘百越’ (Bao Yue) or ‘Hundred Yue’. When Ch’an Master Hongren (弘忍) learned Hui Neng was from ‘Lingnan’ - he jokingly accused him of being an unenlightened ‘barbarian’ and enquired as to whether such a being possessed the ‘Buddha-Nature’? Even if a ‘barbarian’ possessed the ‘Buddha-Nature’, could such a ‘sullied’ being ‘realise’ its empty-essence? Hui Neng calmly replied ‘Humanity is limited to the concept of North and South – whilst Buddha-Nature is beyond such dualistic concepts! Even if the sullied mind and body of a wild barbarian is different from that of a ‘pure’ monk – no such difference exists within the all-embracing Buddha-Nature! Although Hui Neng was young – Hongren understood that he was a very special person.

ACW (6.5.2022) When Charles Luk (1898-1978) dedicated his life to translating Chinese Buddhist texts into the English language, he had to take into account the level of knowledge about Chinese Buddhism that existed across the Western (that is ‘English-speaking’ world), and balance this assessment with the need to translate accurately - so that the English words chosen conveyed (as near as possible), the genuine meaning of the profound Chinese (Indian) Buddhist (philosophical) terms being rendered. As this was essentially a ‘new’ subject for the Western mind (as Chinese Ch’an Buddhism is a very different subject to that of Japanese ‘Zen’ Buddhism), Charles Luk had to be both ‘accurate’ and ‘adaptable’ without diverting too much into the realm of fatal compromise! By the 1950s and 1960s, the days of Christian missionaries translating ancient Chinese spiritual texts (through an obvious veneer of Judeo-Christian theology) were long gone! The Western mind, in many ways ‘modern’ and ‘secular’ demanded more from its conveyers of unfamiliar knowledge and Charles Luk was ready to meet this challenge!

Born in cosmopolitan Guangzhou at the end the 19th century, not only was he well educated in the Chinese language (where he could read the tens of thousands of Chinese ideograms fluently), he was also equally well educated in the English language to a very high degree! This expertise in both languages allowed him to dedicate his life to accurately translating key Chinese Buddhist (and Daoist) texts whilst living in the British Colony (and later ‘Protectorate’) of Hong Kong (it is significant that he chose not to live in ‘Nationalist’ controlled Taiwan)! Charles Luk chose to live in Hong Kong because he was born in ‘Guangdong’ province – and ‘Cantonese’ (with slight variations) is spoken in both areas. This was because the native (and dominant) Chinese dialect spoken in Guangzhou and Hong Kong was ‘Guangdonghua’ or the ‘Language of Guangdong’ better known in the West as ‘Cantonese’. Although every dialect of the Chinese language uses exactly the same ideograms in its written script (with the odd exception) - the manner in which these identical ideograms are pronounced differs slightly. To the Western-eye, these differences can appear immense – such as the surname ‘Chen’ (陳) is also pronounced ‘Chan’, ’Chin’, ‘Tan’ and ‘Van’, etc, but to the Chinese-ear – these differences are very slight and simply denote the geographical location of the origin of the ‘accent’ being used by the speaker! In other words, although the differences look stark and distinct due to the very different ‘phonetic’ lettering used to convey these dialectical differences in the English language, for Chinese-speakers the differences hardly matter at all! This is important background information for the general reader as the point of this article covers how a number of American and British publishers often interfered in Charles Luk’s translations, inserting or omitting paragraphs (here and there) to justify various editing decisions (as confirmed by Charles Luk himself, when discussing this issue with his key British disciple - Richard Hunn [1949-2006]. Richard Hunn subsequently conveyed this important information to me in the early 2000s). One example is the adding of ‘Zen’ to the titles (and texts) of his books which Charles Luk wanted to avoid - as his work had nothing to do with the Japanese ‘Zen’ tradition which he knew very little about and which had done so much damage (in its ‘distorted’ form) before and during WWII actively aiding and encouraging Japanese militarism (see Brian Victoria’s ‘Zen At War’ for a comprehensive explanation, but also Charles Luk’s English translation of Master Xu Yun’s [1840-1959] autobiography - ‘Empty Cloud’ - which includes many first-hands accounts of Imperial Japanese atrocities). Throughout Charles Luk’s translations, Western publishers attempted to involve Charles Luk in the anti-China politics of the US Cold War - forcing additions or omissions about subjects I do not wish to go into in this article. The main point here, is that Charles Luk had been developing his policy to preserve Chinese Buddhism ever since the ‘Nationalist’ Revolution of 1911 due to its pro-Western stance, its allowing of mass Christian missionary work and the exercising of its policy which involved the demolishing of Buddhist and Daoist Temples to make way for hospitals, houses and schools! Cen Xue Lu (1882-1963) - who was the Chinese-language editor of the autobiography of Master Xu Yun - admitted in his biography that when he worked in the ‘Nationalist’ government – part of his job was the ear-marking of various temples (and religious centres) for destruction as a means of making room for modern buildings and as a means of ‘freeing’ China from its spiritual past! After meeting and talking with Master Xu Yun, Cen Xue Lu converted to Buddhism and denounced the ‘Nationalist’ policy of temple destroying – stating that there was ample space throughout China to build hospitals, schools and houses without destroying China’s spiritual past! The Imperial Japanese Forces began their military attack upon China’s culture in 1931, which led to Charles Luk visiting Christmas Humphreys in 1935 and requesting his help in ‘preserving’ Chinese Buddhism. At this time, Christmas Humphreys said ‘no’ - stating that he much preferred Japanese Buddhism (and its militarised ‘Zen’) to Chinese Buddhism (and its ‘Ch’an’) and was not much bothered if it died-out under the Japanese jackboot! All of this has to be mentioned so that it is understood that Charles Luk was campaigning in the name of Chinese Buddhism long before the ‘Socialist’ government was established in China during 1949! From many of the publishers’ ‘Notes’ and added comments through his books published in the post-WWII period – the false impression is made that the government of ‘New’ China was the only reason Charles Luk had started his preservation work – but it is important to remember that Master Xu Yun lived in ‘New’ China until his passing in 1959, whilst Charles Luk refused to live in Taiwan (known as the ‘Republic of China’ post-1949), and much preferred Hong Kong! Indeed, for decades prior to 1949, Charles Luk considered the ‘Nationalist’ government of China (which had destroyed the famous Shaolin Temple in 1928), as well as Japanese Militarism – to be the greatest threats to the survival of Chinese Buddhism! Chiang Kai-shek, of course, was a Christian convert who did not lose much sleep over the idea of the demise of Chinese Buddhism! In the late 1950s, Charles Luk is accredited with making the following statement – which appears to be an anti-China ‘racist’ statement formulated by a non-Chinese person with no genuine knowledge of the Chinese-language - but there is very good reason to believe he never wrote this (as he told Richard Hunn as much), and that it is a product of a publisher’s interference and ignorant imagination: ‘It is due to a mispronunciation of the Patriarch’s name in Cantonese ‘Wei Lang’ by the late Mr. Wong Mou Lam, who translated the Altar Sutra some thirty years ago that it is now widely known in the West as the Sutra of Wei Lang. Wong Mou Lam was a Cantonese and there are in South China some people who cannot spell correctly a name beginning with the letter “n”.’ Charles Luk: Ch’an and Zen Teaching – Third Series, Rider, (1962), Page 14 - ‘Foreword’, Hong Kong, (August, 1958). As Charles Luk was a ‘Cantonese’ person - why would he have written this ridiculous statement? Indeed, it appears to be written by a non-Chinese person with no knowledge of the Chinese language. The name written as ‘Wei Lang’ (惠能) - is the ‘correct’ pronunciation of these two Chinese ideograms in the Cantonese dialect (this is an important observation, as the man known as ‘Hui Neng’ today – was born in Guangdong province – making him a ‘Cantonese’ person). Interestingly, although Wong Mou Lam was also a ‘Cantonese’ person – when he produced his ground-breaking translation of the Altar Sutra – it was published in Shanghai. This is what Christmas Humphreys has to say about Wong Mou Lam: ‘The first, and apparently the only published translation into English of the Sutra of Wei Lang was completed by the late Mr. Wong Mou-Lam in 1930, and published in the form of a 4to paper-covered book by the Yu Ching Press of Shanghai. Copies were imported to London a few dozen at a time by the Buddhist Lodge, London (now the Buddhist Society, London), until 1939, when the remaining stock was brought to England and soon sold out. The demand, however, has persisted; hence this new edition. Mr. Alan Watts, the author of the Spirit of Zen, and other works on Zen Buddhism, has pressed for the adoption of the Sixth Patriarch’s name Hui Neng, instead of Wei Lang. It is true that he is so referred to by such authorities as Professor DT Suzuki, but most Western students already know the work as the Sutra of Wei Lang, and the translator used this dialect rendering throughout the work. I have therefore kept to the name best known to Western readers, adding the alternative rendering for those who know him better as Hui Neng.’ Wong Mou Lam: The Sutra of Hui Neng - Sutra Spoken by the 6th Patriarch of the High Seat of “The Treasure of the Law”, San Yang, (1952), Pages 5 – 7 - ‘Foreword’, Christmas Humphreys (December, 1952) In 1644, the Manchurian (Jurchen) people of Northeast China established the ‘Qing’ Dynasty and relocated its capital from ‘Mukden’ to ‘Beijing’. As the Manchus recruited local Chinese-scholars in Beijing to serve in the imperial palace and the ‘Qing’ government – the Manchus decided that the governing ‘official’ language of China would be the Beijing dialect. When the ‘Qing’ collapse in 1911, the new ‘Nationalist’ government continued to use this ‘official’ language whilst also experimenting with a broader use of English in diplomatic exchanges, etc. Neither the ‘Qing’ nor the ‘Nationalists’, however, made any great efforts to reduce the illiteracy rate in China (which remained steady for centuries with only about 10% of the population being able to read and write). In 1955, the government of ‘New’ China formally recognised a modified version of the Beijing dialect now termed ‘Putonghua’ (普通話) or ‘Public Usage Language’. This language was taught throughout China in all the schools, colleges and universities, and became known as the ‘Standard’ Chinese language (although still referred to in the West as ‘Mandarin’). Prior to this date (and the embarking upon the mass literacy campaigns), the use of other dialects in China was not only common, but to be expected. When Wong Mou Lam compiled his translation of the Altar Sutra around 1938, as ‘Cantonese’ was the dialect he spoke, expressing the sixth Patriarch’s name (惠能) as ‘Wei Lang’ was perfectly acceptable. Furthermore, neither the name ‘Hui Neng’ or ‘Wei Lang’ begins with an “n” as suggested in the above extract attributed to Charles Luk! Hui Neng (638-713 CE) carried the surname of ‘Lu’ (盧) - whilst his mother’s maiden-name was ‘Li’ (李). His father (Lu Xingyuan - ‘盧行瑫’) originally held an official post in ‘Fanyang’ (范阳) - now Zhuozhou City, Hebei Province – but due to a scandal (which could have been anything – including a change in policy, differing trends, or ascribed ‘blame’, imagined or otherwise) was dismissed from his post and banished to Guangdong province to live as a ‘commoner’ with no rank, employment or responsibility (as scholar-officials were routinely ‘executed’ for any reason whatsoever, this punishment might well have been considered ‘mild’ by comparison). It was here, in what was then called ‘Lingnan’ (岭南) that Hui Neng was born – and his father passed away soon afterward. Indeed, today this area equates to Xinxing County, Guangdong province. During the Tang Dynasty, this was considered a ‘frontier’ area where ethnic Chinese people confronted what were considered to be non-Chinese ‘barbarian’ people who lived ‘outside’ of the structures of Chinese culture and governance! This explains why Hui Neng – whose family were actually ethnic Chinese people from North China – were sometimes considered to be ‘non-Chinese’ (although as the centuries rolled by, ALL ethnic groups that inhabit geographical China would become ‘integrated’ into the Chinese Nation)! His name of ‘Hui Neng’ (惠能), however, is not his first-name given at birth, but rather appears to be a ‘Buddhist’, or ‘Dharma’ name given to him at a later date by a Buddhist monastic or Buddhist teacher, etc. This is known because ‘惠’ (hui4) in Putonghua and (wai6) in Cantonese can be translated as ‘bestower’, ‘benefiter’, and ‘kindliness’, whilst ‘能’ (neng2) and (nang4) means ‘ability’, ‘capability’ and ‘energetic’, etc. Hui Neng’s name probably suggests the meaning of ‘Bestower of Energetic Ability’ or perhaps ‘Kind Enabler’, etc. What is interesting is that if the ‘Northern’ (Beijing) dialect of his father is taken into account, then the name of his son - ‘惠能’ - would be more properly pronounced as ‘Hui Neng’ - but as his son was born in Guangdong province amongst the Southern people living there, then it would be perfectly logical for the name of ‘惠能’ to be pronounced as ‘Wei Lang’ or ‘Wai Lang’ - although as I said before – these differences are ‘slight’ when viewed from the perspective of the Chinese language! Chinese-language Buddhist records state that the Sixth Patriarch received the Dharma-Name ‘惠能’ (Hui Neng) from two different Buddhist monks who separately visited his home during his young childhood. His father died when he was three-years-old – and he and his mother moved to Nanhai (or ‘Guangzhou’ - the same place Charles Luk was born). He grew-up making a living selling fire-wood in the local market-place. He left home after his mother passed away – or in another version of the story – after relatives paid money for the upkeep of his mother and arranged alternative sources of care for her. When he attained enlightenment (after hearing the Diamond Sutra or perhaps the Mahaparinirvana Sutra – or both - being chanted), he was a ‘layman’ and did not ordain as a monk until the year 667 CE – or when he was thirty-years-old (although the exact details vary depending upon the versions being accessed). He left home to seek Ch’an instruction in 661 CE (when he was twenty-four-years-old). From 662-667 CE (between the ages of twenty-five and twenty-nine) Hui Neng entered five-years of secluded meditational practice. He was ordained in 667 CE and passed away in 713 CE at the age of seventy-six-years-old. In all of this time he lived-in and moved-around Guangdong province where the prevailing dialect is ‘Cantonese’. ©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2022. Chinese Language References: https://baike.baidu.com/item/惠能/949488 https://baike.baidu.com/item/岭南道/4187968 https://baike.baidu.com/item/越/22559 |