|

Buddhist monasticism is flexible. Although it is correct to assume that it is usually necessary for an individual to undergo a period of isolatory training (to establish and stabilise the realisation of the void) - it is also true that compassionate (Bodhisattva) activity must also be pursued throughout the myriad conditions that define worldly existence. This is true of all Buddhist traditions - as even the Bhikkhus of the Theravada School must "walk" (in a self-aware manner) through the surrounding (lay) villages - begging for food on a daily basis. Living a hermitic or cloistered existence is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Of course, this period may be repeated more than once and last any length of time. When entering different situations - the Bodhisattva does not lose sight of the realised void regardless of the external conditions experienced. The Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) spent around 15 years living with bandits and barbarians in the hills - retaining a vegetarian diet - even though he was not yet formally ordained in the Sangha. Within China, the Mahayana Bhikshu must take the hundreds of Vinaya Discipline Vows as well as the parallel Bodhisattva Vows (the former requires complete celibacy whilst the latter requires moral discipline but not celibacy). Anyone can be a "Bodhisattva" - whilst a formal Buddhist monastic must adhere to the discipline of the Vinaya Discipline. A lay Buddhist person also adheres to the Vinaya Discipline - but only upholds the first Five, Eight or Ten vows, etc. Vimalakirti is an example of an Enlightened Layperson whose wisdom was complete and superior to those who were still wrapped in robes and sat at the foot of a tree. In the Mahasiddhi stories preserved within the Tanrayana tradition - the realisation of the empty mind ground (or all-embracing void) renders the dichotomy between "ordained" and "laity" redundant. The Chinese-language Vinaya Discipline contains a clause which allows, under certain conditions, for an individual to self-perform an "Emergency" ordination. This is the case if the individual lives in isolation and has no access to the ordained Sangha or any other Buddhist Masters, etc. The idea is that should such expertise become available - then the ordination should be made official. However, the Vinaya Disciple in China states that a member of the ordained Sangha is defined in two-ways: 1) An individual who has taken both the Vinaya and Bodhisattva Vows - and has successfully completed all the required training therein. 2) Anyone who has realised "emptiness". Of course, in China all Buddhists - whether lay or ordained - are members of the (general) Sangha. The (general) Sangha, however, is led by the "ordained" Sangha. As lay-people (men, women, and children) can realise "emptiness" (enlightenment) - such an acommplished individual transitions (regardless of circustance) into the "ordained" Sangha. This is true even if such a person has never taken the Vinaya or Bodhisattva Vows - regardless of their lifestyle or position within society. Such an individual can be given a special permission to wear a robe in their daily lives - but these individuals do not have to agree with this. Realising "emptiness" is the key to this transformative process. Emptiness can be realised during seated meditation, during physical labour (or exercise), or during an enlightened dialogue with a Master. The first level is the "emptiness" realised when the mind is first "stilled". This "emptiness" is limited to just the interior of the head - but the ridge-pole of habitual ignorance has been permanently broken (this is the enlightenment of the Hinayana) - and is accompanied by a sense of tranquillity and bliss. This situstion (sat atop the hundred-foot pole) must be left behind. Through further training, the "bottom drops out the barrel" - and the perception of the mind expands throughout the ten directions. Emptiness embraces the mind, body, the surrounding environment - and all things within it.

0 Comments

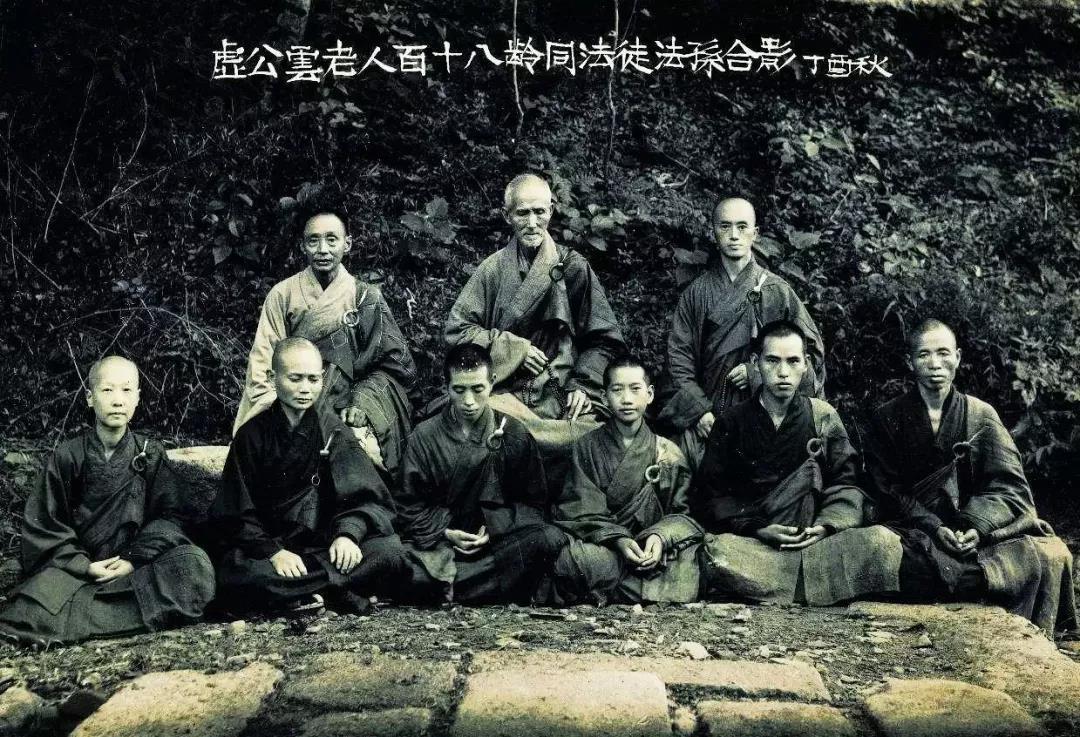

Richard Hunn (Wen Shu) was NOT keen on any notion of ‘Transmitting’ the Ch’an Dharma. This coincided with his attitude of NOT wanting to be associated with any particular University, Publisher or Dharma Group, etc. I agree with this approach. Dogma, idealism and superstition has nothing to do with genuine Chinese Ch’an Buddhist practice. What an individual does with their mind (and body) regarding attitudes and opinions held concerning life, politics, culture or everyday activities – has absolutely NO interest for the genuine Chinese Ch’an Master! This attitude is encountered time and again throughout the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties Ch’an writings of Imperial China – with Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) carrying-on this attitude into the post-1911 era of ‘modern’ China! Obviously, I have NOTHING to transmit. Teaching is simply taking the conditions that already exist – and turning the awareness of the enquirer back toward the ‘empty mind ground’ from which all perception arises (and ‘returns’ according to the Chinese Ch’an tradition) - this is a ‘transmission’ in a general sense – but such an interaction cannot be interpreted as an individual in the West being granted ‘Transmission’. Within Chinese culture, such ‘Transmission’ was Confucian in origin and often travelled within birth families and specific name clans – very seldom (if ever) was a ‘Transmission’ initiated ‘outside’ the family (as ‘outsiders’ could not be trusted to use the family secrets of spirituality, science and martial arts properly). Later, when the ‘Transmissions’ of (related) ‘Father to Son’ was adjusted to accommodate (non-related) ‘Masters to Disciples’ - outside ‘Transmissions’ (separate from the Confucian birth-process) was developed. This is the agency of continuation from generation to generation preserved within the Chinese Ch’an tradition. Birth-relationship is replaced with a ‘strict’ attitude of ‘respect’ and the maintaining of ‘good’, ‘correct’ and ‘appropriate’ decorum, behaviour and deportment. Even within ‘modern’ China – this is a difficult interaction to a) perform and b) achieve. The standards for keeping the mind and body permanently ‘clean’ night and day and is often viewed as being far too difficult for the average individual to meet. As ‘Transmission’ is NOT a game and given that ‘Transmission’ within the Chinese Ch’an tradition is NOT the same as ‘Transmission’ within the Japanese Zen tradition – it is obvious that when the Chinese Ch’an tradition ‘flows’ into the West – it is NOT the case that ‘Transmission’ can easily be applied. The empty mind ground must be ‘realised’ (not an easy task) and ‘maintained’ in every situation (an even more unlikely achievement). I have experimented with ‘Transmission’ in the West – but have found that as soon as the event unfolds – an IMMEDIATE ‘dropping away’ of all interactive effort, respect and continuation occurs. This means that the crucial and inherent energy is diminished, sullied and obscured - and the Ch’an lineage loses its clarity, understanding and ability to ‘free’ others. This explains ‘why’ I have eventually WITHDRAWN all so-called ‘Transmissions’ as a means to emphasis the recorded activities of the Chinese Ch’an Masters – written down in China and translated into English by Charles Luk [Lu Kuan Yu] (1898-1978). Granting Chinese language Dharma-Names and formally ‘Welcoming’ individuals into the ‘Lineage’ - does NOT constitute a ‘Transmission’. As helping others is a key element of the Bodhisattva Vow – I do NOT wish to inadvertently ‘damage’ the Chinese Ch’an tradition entrusted to me – by generating what amounts to a ‘dysfunction’ of transmission.

The Buddha explains clearly, in every expression of his teaching, that consciousness and physical matter are not two different things, even though they may be viewed as two distinct expressions of the same underlying reality. This understanding avoids the traps of ‘idealism’ and gross ‘materialism’, which are both declared errors by the Buddha. It is not that the mind does not exist, or that the physical world does not exist – both definitely do within an interpretive context – but that attachment to one view or the other is unhelpful when it comes to meditational development and the cultivation of wisdom. Furthermore, within the Four Noble Truths, it is clear that ‘consciousness’ in the chain of becoming has ‘physical matter’ as its basis (I.e. matter, sensation, perception, thought formation and conscious awareness). If this was not the case, this chain would read ‘conscious awareness’, ‘thought formation’, ‘perception’, ‘sensation’ and ‘matter’ - but it does not. This is the error made by DR DT Suzuki in his commentary upon the Lankavatara Sutra, which is perpetuated by those who think the Yogacara School is ‘idealist’ - when in fact the founders of this school begin their analysis by firmly stating that they agree with the Buddha when he says that the human mind is ‘impermanent’. Besides, genuine Buddhist training is as much in the mind as it is in the body, with ‘sila’ (morality) being the control of thought and physical behaviour. The ‘stilling’ of the mind is as important as the ‘stilling’ of the body, although the former supersedes the latter with regard to transformation and perception thereof. However, for a human mind to be functional, it must be existent within a living body. As to what might happen ‘before birth’ and ‘after death’, the Buddha remains ‘silent’, with many people utilising the metaphysics of religion to fill in this void...

The body is disciplined so that the mind may be ‘focused’. The Buddha teaches a type of Yoga, or at least a path that is recognisably ‘Yogic’ in origination. One of the first lines of the Patanjali Sutra reads ‘Yoga is the restriction of the fluctuations of consciousness.’ (Feuerstein 1989). Yoga is also an umbrella term used to describe a profound mind and body training that generates a permanent psycho-physical transformation. This is not a ‘subjective’ delusion, as the Buddha warns against this misidentification of inner awareness, and neither is it a hedonistic attachment to external pleasures (or pain) depending upon the conditionality of an individual. The Buddha advocates a non-identification with thought (and feeling), and a detachment from all physical sensation. Although there is a stage whereby the mind becomes free of surface thought (and a ‘stillness’ is experienced), nevertheless, eventually the process of thought is re-born in the mind but in an entirely ‘new’ manner which no longer ‘obscures’, ‘confuses’ or induces any form of ‘suffering’, etc. (The post-enlightenment situation is controversial and open to debate.) Being a ‘Bodhisattva’ requires an individual to become truly ‘universal’ in perception, understanding and empathy. The conundrum of personal suffering must be solved before the suffering of the entire world can be taken on without any form of hindrance. To be a genuine Bodhisattva, is to be able to take responsibility for every single mode of suffering that exists in this world and the worlds beyond. Universal suffering is not limited to only that which humans feel – but necessarily includes ALL suffering everywhere. Furthermore, the committed Bodhisattva willingly takes on the suffering of past, the present and the future. The ‘intention’ is to be with those who are experiencing suffering, and to spiritually offer support and sustenance to help them through that which most would find difficult to experience or even face. How this is to be achieved is entirely dependent upon circumstance as there is no single method that meets all requirements. This is not an easy ability to achieve or function to perform. This is why Buddhist monastics in China take the ‘Bodhisattva Vows’ as well as the ‘Vinaya Discipline’ as part of their spiritual responsibilities. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed