|

There is a significant difference between the falling into the state of ‘dull’ nothingness (as warned against by Master Xu Yun) and the realisation of genuine ‘emptiness’ within traditional Chinese Ch’an training. The difference must be properly understood if progression is to be made. a) ‘Nothingness’ (Pali 'Akincanna’) - or ‘No-Something-Ness' - is the falling into ‘dull’ nothingness often mistaken as the realisation of genuine ‘emptiness’ and ‘enlightenment’ - which is still ‘post-thought’ in manifestation. b) The realisation of genuine ‘Emptiness’ (Pali ‘Sunnata’) or relative enlightenment is ‘pre-thought’ - as the empty mind ground is what is perceived when no thoughts arise. What does this mean? Dull nothingness (akincanna) is a thought form with a non-descript content. In other words, a thought is generated which is defined by the usual boundaries and parameters that constitute the average structured ‘thought’ form - but the meditator misunderstands this ‘non-descript’ content and mistakenly grasps it as being the empty mind ground. The trap here is that a manifest ‘thought’ (and stream of thought) is masquerading as the psychic fabric from which all structured thought arises – and which pre-exists all thought. This state is mistaken as complete and perfect enlightenment and those trapped within it start misleading others down the wrong path. By way of contrast, the state of genuine ‘emptiness’ (sunnata) is realised when all thought generation ‘ceases’ at its source – and the empty mind ground manifests and becomes apparent as its presence is no longer obscured by the continuous stream of thought which normally traverses the surface mind. No thoughts arise whatsoever and so the empty mind ground becomes perceivable. As there is a sense of ‘constriction’ - this genuine state of ‘emptiness’ realisation is termed ‘Sitting atop a hundred-foot pole’ (which is symbolic of Hinayana enlightenment), as it is accompanied by a sense of ‘peace’ and ‘tranquillity’ - but a further stage of training is required.

0 Comments

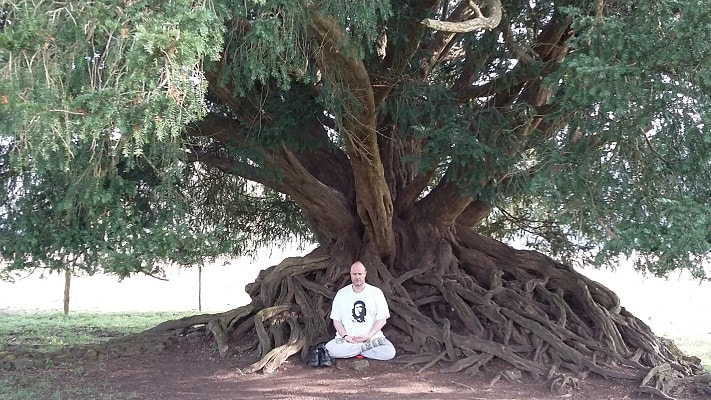

Author’s Note: In 2017, I wrote a short article about the Pali term ‘Bhavana’ and since then, I have been asked to write a more in-depth article regarding the meaning and application of this term in its Pali and Sanskrit context (both different and yet overlapping in places). Whereas in my earlier article (referenced below) I focused a great deal on the Chinese language term for ‘bhavana’ - in this outing I have limited myself to just the briefest of references to the Chinese equivalent – an act of considerable will-power considering Chinese Buddhism is one of my academic specialities (both ethnically and academically). However, I have always held the Theravada tradition in high regard and have been helped tremendously by its many practitioners and institutions around the world! From my Chinese Ch’an practice (and penetration of the empty mind ground) - I have come to see and appreciate how the many different branches of Buddhism (and reality in general) all manifest from the same stout trunk... Although what I convey to you is academically correct – you do not have to accept my conclusions. Always think for yourselves and make-up your own minds! ACW (17.9.2021) When I was studying Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka (in 1996), a term I came across continuously was ‘bhavana’ (‘भावना’ Pali and ‘भवन’ Sanskrit) - this was invariably used to refer to the act of seated ‘meditation’ and all the psychological and physical discipline required to successfully carry-out this important Buddhist practice. Indeed, within the Chinese written language, ‘bhavana’ is referred to as ‘修習’ (Xiu Xi) - or a central method of mind-body transformation – literally ‘self-cultivation method(s) or ‘habits’’ or ‘disciplined paths which intersect at a certain point of development’. A more succinct translation could be ‘paths of self-discipline' with the caveat that what is being suggested is the strict disciplining of the mind and body through the correct application of the Vinaya Discipline and the Bodhisattva Vows. Therefore, the single act of seated meditation has a wealth of supporting disciplinary activities surrounding its application, and does not appear does not suddenly appear out of a vacuum of non-effort. In other words, ‘bhavana’ refers to an act of ‘meditation’ which is the summation of the entire Buddhist path! Although the emphasis was always upon seated meditation, of course, standing, sitting and lying-down is allowed in the Buddhist Suttas – which very much depends upon the meditation teacher and the practitioner involved. Compassion, loving-kindness and wisdom must always be the driving force behind the practice of ‘bhavana’. As a ‘noun’, the Sanskrit dictionary states that भवन (bhavana) refers to:

The Pali dictionary suggests that ‘bhavana’ (भावना) refers to 'mental development' (lit. 'calling into existence, producing') in what in English is generally referred to 'meditation'. The Theravada School of Buddhism distinguishes two types of bhavana:

Interestingly, the very similar Sanskrit term ‘भावना’ (bhāvnā) refers to feeling, sensation, emotion and sentiment and is certainty moving toward the Buddhist (Pali) implications. Perhaps the Buddha modified a Pali term which once referred to the external practice of building houses and cultivating fields for farming – but changed its onus from this ‘objective’ meaning to a purely ‘subjective’ meaning relating to states of mind and patterns of thought and emotion. Just as rocks, weeds and stones are removed from the soil to make it fertile – the Buddhist practitioner uproots greed, hatred and delusion from the psychic fabric of the mind so that the mind becomes ‘fertile’ to receive the fruits of Buddhist self-cultivation. The Pali term appears to be referring to ‘that which arises from within’ - whilst the Sanskrit term is referring to ‘that which arises from without’. I would suggest that the inner perception of boundless space integrates with the awareness of boundless outer space – and that this is how the Buddha ultimately reconciles the two distinct meanings of this term. If a practitioner applies the Dhamma correctly – then like a plant growing from a seed into a might tree – the fruits of the Dhamma will manifest in the mind, body (and through behaviour) the environment!

Dear B

The Buddhist Sutras state that at the point of enlightenmet realisation - all karmic activity ceases and all gods-goddesses are understood to be non-existent. Indeed, the only karma left is the lifespan of the current human-body - which must be lived-out - but with any potential (debilitating) effects greatly diminished through the - volitionl capacity of subject-object attachment - being transcended. Of course, this matter is complicated by the Bodhisattva principle which states that an appropriate 'deluded thought' is produced at the point of physical death so as to initiate yet another bodily existence (through force of habit) - which is selflessly used to help all other life-forms - whatever they may be (human, animal, environment and alien, etc). Pali scholars suggest this Mahayana teaching is 'nonsense' - whilst Mahayanists consider it natural and inevitable - take your pick. However, when an existence is completely 'finished' (as with Buddha and Master Xu Yun) - the individual concerned enters 'parinrivana' and that is very much that. Remember, the gong-an (koan) literature contain a wealth of wisdom regarding these matters. When enlightened Masters are asked what they have been practicing of late - they often reply 'not even the four noble truths.' Why practice an expedient teaching when one's mind (and body) exists in a permanent state of integration with the ultimate position (i.e. the 'empty mind ground')? |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed