|

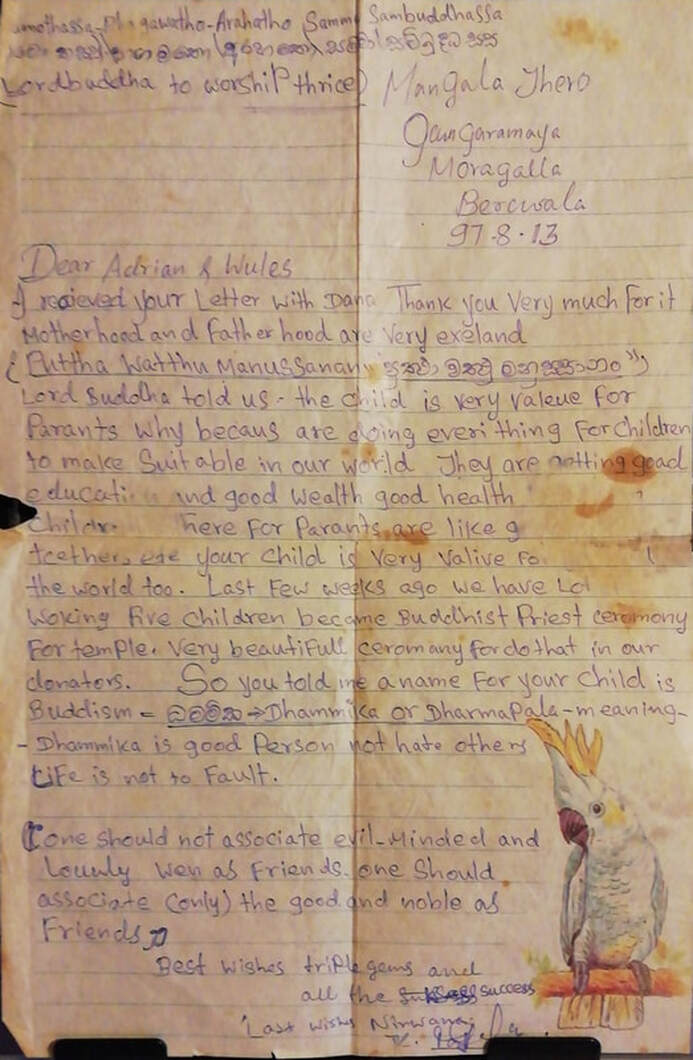

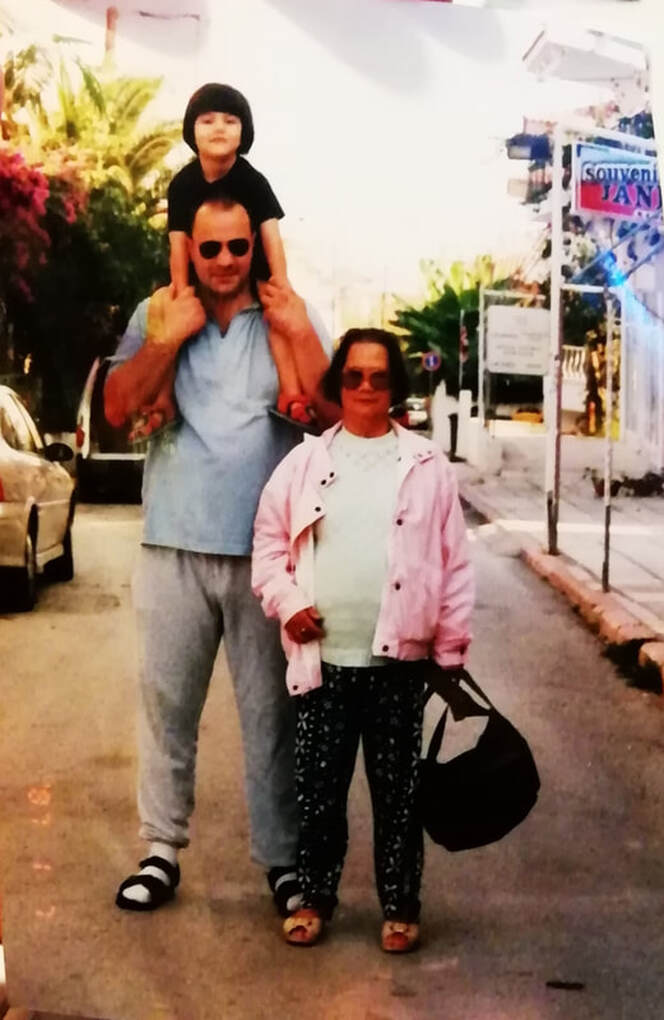

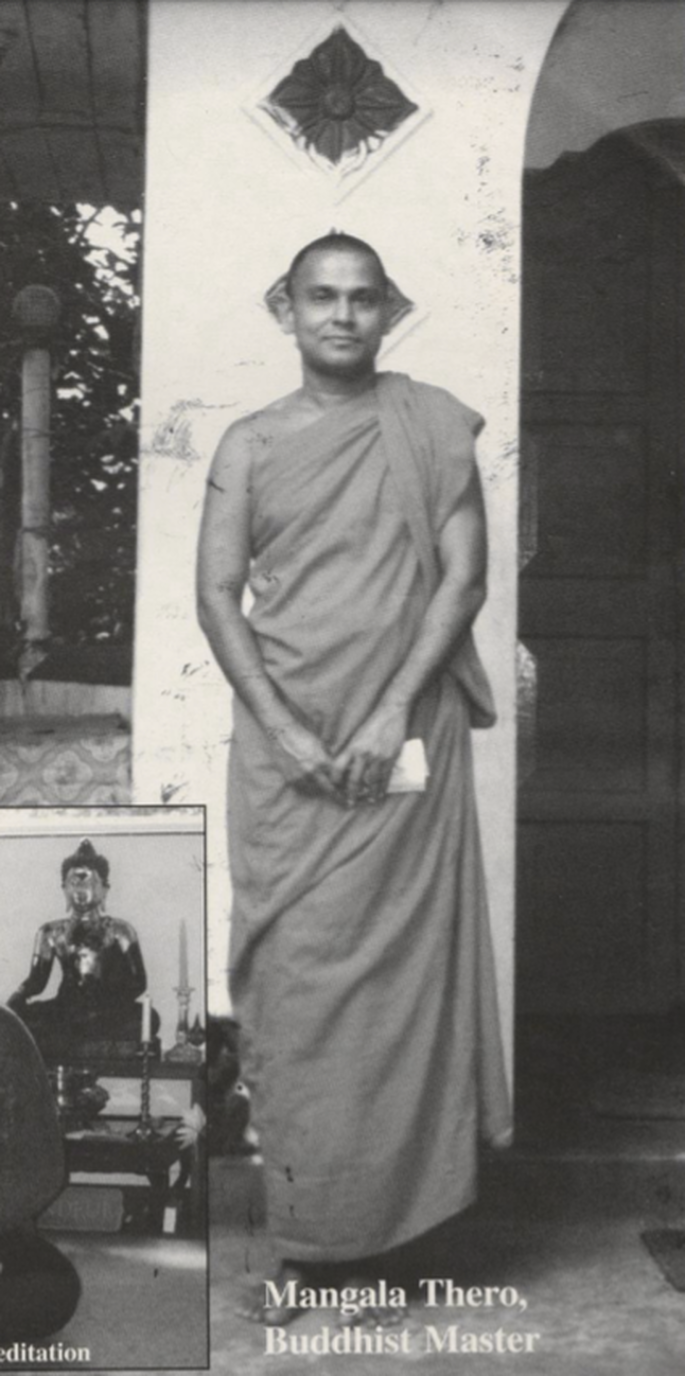

My oldest daughter - Sue-Ling-Chan-Wyles - was born on August 8th, 1997. I was married to her mother - Cindy Chan - in Beruwela, (Sri Lanka) on December 13th, 1996. The Venerable Mangala Thero (a very learned Theravada Buddhist Monk now deceased) gave Sue-Ling the Dharma-Name 'Dhammika' - or 'She Who Diligently and devotedly Adheres to the Dhamma'. The Buddha advised a follow of His Dhamma to 'avoid' mixing with evil or negative persons - as their psychological and physical 'taints' (kilesa) or negative karma generated by excessive greed, hatred and delusion. Such people must help themselves - with those already possessing a pure mind (that is beyond corrupt) assisting them in this task. Those still attempting to purify and stabilise their minds must - for a time - separate themselves from the masses until their minds are strong enough to truly help and assist others. Sue-Ling is a grown woman now finding her own way in the world - and she is engaged in a number of ongoing projects designed to help and assist many different people. This is the ;essence' of Dhamma!

0 Comments

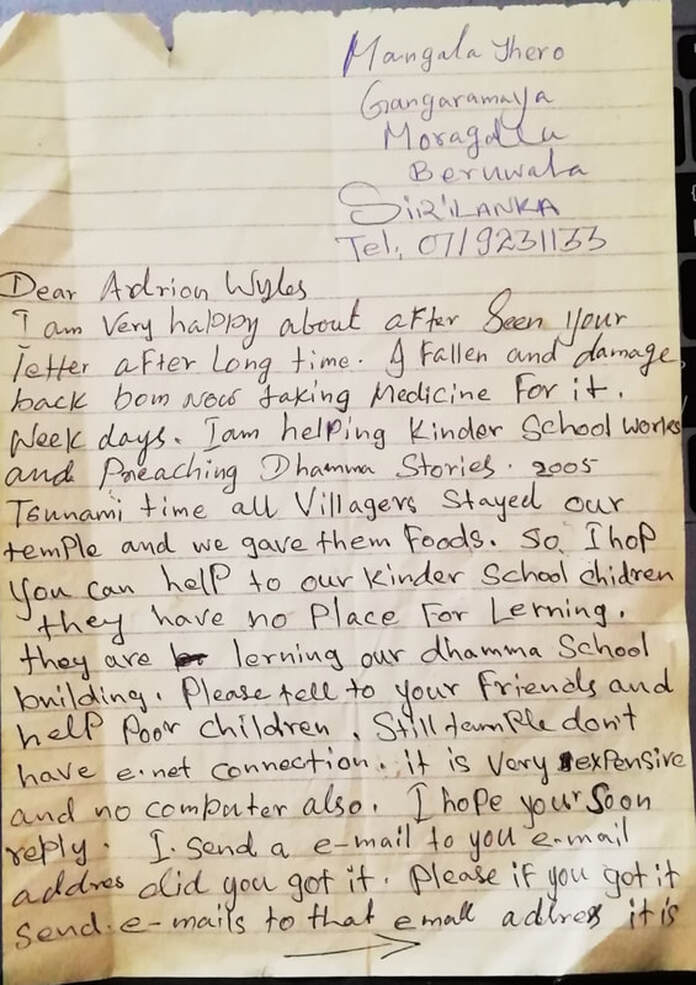

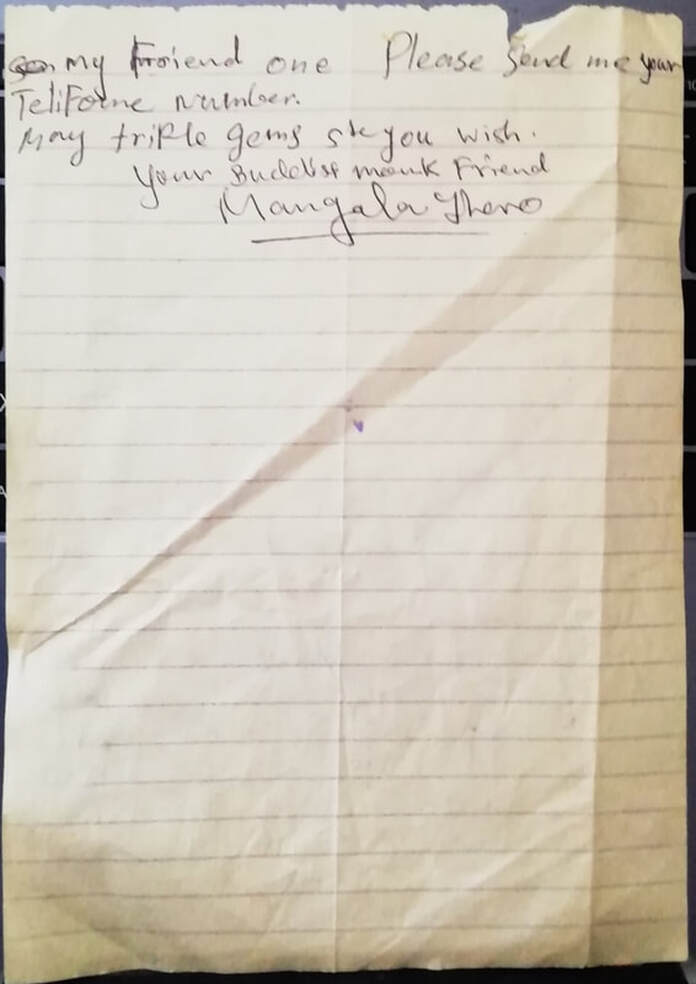

Over a number of weeks, Mangala Thero introduced me to the fundamentals of the Theravada School as taught in Sri Lanka. When returning to the UK - I had him featured in a Taijiquan magazine. However, some years later (around 2005), the Ven. Mangala Thero set me the following letter:

Author’s Note: In 2017, I wrote a short article about the Pali term ‘Bhavana’ and since then, I have been asked to write a more in-depth article regarding the meaning and application of this term in its Pali and Sanskrit context (both different and yet overlapping in places). Whereas in my earlier article (referenced below) I focused a great deal on the Chinese language term for ‘bhavana’ - in this outing I have limited myself to just the briefest of references to the Chinese equivalent – an act of considerable will-power considering Chinese Buddhism is one of my academic specialities (both ethnically and academically). However, I have always held the Theravada tradition in high regard and have been helped tremendously by its many practitioners and institutions around the world! From my Chinese Ch’an practice (and penetration of the empty mind ground) - I have come to see and appreciate how the many different branches of Buddhism (and reality in general) all manifest from the same stout trunk... Although what I convey to you is academically correct – you do not have to accept my conclusions. Always think for yourselves and make-up your own minds! ACW (17.9.2021) When I was studying Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka (in 1996), a term I came across continuously was ‘bhavana’ (‘भावना’ Pali and ‘भवन’ Sanskrit) - this was invariably used to refer to the act of seated ‘meditation’ and all the psychological and physical discipline required to successfully carry-out this important Buddhist practice. Indeed, within the Chinese written language, ‘bhavana’ is referred to as ‘修習’ (Xiu Xi) - or a central method of mind-body transformation – literally ‘self-cultivation method(s) or ‘habits’’ or ‘disciplined paths which intersect at a certain point of development’. A more succinct translation could be ‘paths of self-discipline' with the caveat that what is being suggested is the strict disciplining of the mind and body through the correct application of the Vinaya Discipline and the Bodhisattva Vows. Therefore, the single act of seated meditation has a wealth of supporting disciplinary activities surrounding its application, and does not appear does not suddenly appear out of a vacuum of non-effort. In other words, ‘bhavana’ refers to an act of ‘meditation’ which is the summation of the entire Buddhist path! Although the emphasis was always upon seated meditation, of course, standing, sitting and lying-down is allowed in the Buddhist Suttas – which very much depends upon the meditation teacher and the practitioner involved. Compassion, loving-kindness and wisdom must always be the driving force behind the practice of ‘bhavana’. As a ‘noun’, the Sanskrit dictionary states that भवन (bhavana) refers to:

The Pali dictionary suggests that ‘bhavana’ (भावना) refers to 'mental development' (lit. 'calling into existence, producing') in what in English is generally referred to 'meditation'. The Theravada School of Buddhism distinguishes two types of bhavana:

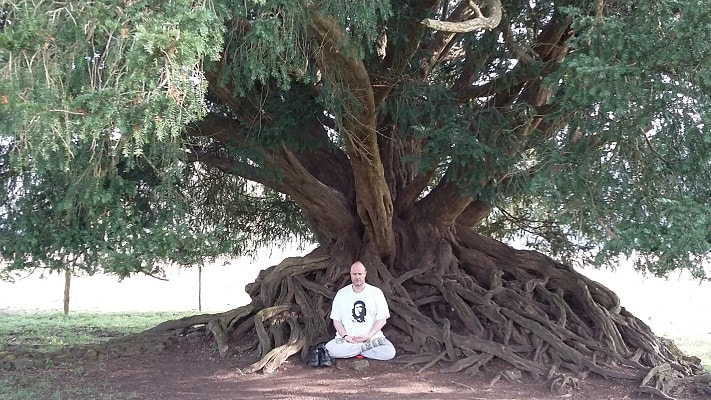

Interestingly, the very similar Sanskrit term ‘भावना’ (bhāvnā) refers to feeling, sensation, emotion and sentiment and is certainty moving toward the Buddhist (Pali) implications. Perhaps the Buddha modified a Pali term which once referred to the external practice of building houses and cultivating fields for farming – but changed its onus from this ‘objective’ meaning to a purely ‘subjective’ meaning relating to states of mind and patterns of thought and emotion. Just as rocks, weeds and stones are removed from the soil to make it fertile – the Buddhist practitioner uproots greed, hatred and delusion from the psychic fabric of the mind so that the mind becomes ‘fertile’ to receive the fruits of Buddhist self-cultivation. The Pali term appears to be referring to ‘that which arises from within’ - whilst the Sanskrit term is referring to ‘that which arises from without’. I would suggest that the inner perception of boundless space integrates with the awareness of boundless outer space – and that this is how the Buddha ultimately reconciles the two distinct meanings of this term. If a practitioner applies the Dhamma correctly – then like a plant growing from a seed into a might tree – the fruits of the Dhamma will manifest in the mind, body (and through behaviour) the environment!

What is the point of Ch’an (or Buddhist) enlightenment in the modern age? Many, if not all of the world’s great scientific breakthroughs have been made by human minds that have not undergone the Buddhist training, and which have not uprooted greed, hatred or delusion, transcended duality or perceived the empty mind ground. My personal opinion is that Buddhist developmental methodology is not a religion, despite the fact that many manifestations of Buddhism have assumed the garb of religiosity. Buddhism is not anti-science as the theology of other religions is often presented, and yet the Buddha and his disciples (although many of them ‘learned’), could not read or write. Many are surprised by this, but at no point in any of the 5000 plus Buddhist texts does the Buddha mention the modern notion of literacy, despite the Buddha’s thought processes appearing to be very modern despite manifesting at sometime between 2,500-3000 years ago in ancient India. As the concept of modern science has now mainstreamed in the world, together with literacy being the preferred norm, the Buddha’s path no longer seems that special or important. An effective scientist does not need to meditate or gain enlightenment to be an effective servant of humanity, and profoundly assist in its development and welfare. On the other hand, I have read Professors at Oxford University state that in their opinion, the Buddha was the first ‘modern’ thinker at a time when logical thinking was thin on the ground, with Carl Jung opining that the Buddha appeared, through a sheer act of will, to think ‘outside’ the era within which he existed. This on its own is an extraordinary feat, if it is accepted that he was the world’s first modern thinker in the true sense. In today’s world, being intellectually astute is inherently linked to simultaneously possessing a high degree of literacy and coming from an economically rich background, and yet the Buddha had none of these things as a spiritual-seeker. Indeed, today he would be considered one of the homeless community and what he had to say would be deliberately excluded from what is considered the general (and valid) discourse of mainstream existence. It is perhaps ironic that most that refer to themselves as ‘Buddhist’ in the contemporary West are of the privileged economic class that the Buddha rejected. The enlightened Buddha combines poverty, homelessness and unemployment with selflessness, non-attachment and sublime wisdom. What is interesting is that if a person were to live in a peaceful forest or on top of a hill far from the cares of the ordinary world, then the Dharma certainly does prove to be a ‘way out’ of ordinary suffering (by following the Vinaya Discipline). However, within the Ch’an School (and the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra), the Buddha explains the path of the enlightened lay-person. Such a person lives amongst the pleasures and pains of the world and remains non-attached to arising and falling thoughts (and emotions), and is unmoved by words of praise or blame. The empty nature of material reality is always perceived as underlying the continuous play of phenomena. Although a busy street or a quiet mountain top may differ in outward appearances, they both share exactly the same empty mind ground, and other than the practicalities of different manifestations, no real difference can be discerned. Understanding this is the further training required after enlightenment. From my own perspective, training as a young man directed, strengthened and freed the full intellectual and wisdom capacities inherent in my mind, whilst allowing me a completely different way of relating to and controlling my physical body. This led to tremendous academic success and the mastery of our family martial arts system.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed