|

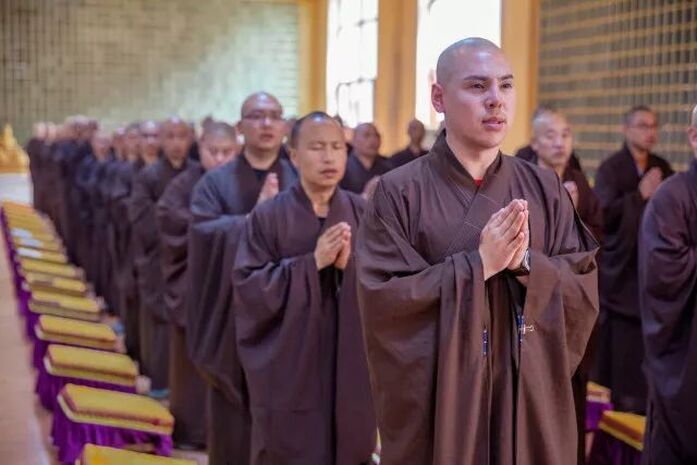

Buddhist monasticism is flexible. Although it is correct to assume that it is usually necessary for an individual to undergo a period of isolatory training (to establish and stabilise the realisation of the void) - it is also true that compassionate (Bodhisattva) activity must also be pursued throughout the myriad conditions that define worldly existence. This is true of all Buddhist traditions - as even the Bhikkhus of the Theravada School must "walk" (in a self-aware manner) through the surrounding (lay) villages - begging for food on a daily basis. Living a hermitic or cloistered existence is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Of course, this period may be repeated more than once and last any length of time. When entering different situations - the Bodhisattva does not lose sight of the realised void regardless of the external conditions experienced. The Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) spent around 15 years living with bandits and barbarians in the hills - retaining a vegetarian diet - even though he was not yet formally ordained in the Sangha. Within China, the Mahayana Bhikshu must take the hundreds of Vinaya Discipline Vows as well as the parallel Bodhisattva Vows (the former requires complete celibacy whilst the latter requires moral discipline but not celibacy). Anyone can be a "Bodhisattva" - whilst a formal Buddhist monastic must adhere to the discipline of the Vinaya Discipline. A lay Buddhist person also adheres to the Vinaya Discipline - but only upholds the first Five, Eight or Ten vows, etc. Vimalakirti is an example of an Enlightened Layperson whose wisdom was complete and superior to those who were still wrapped in robes and sat at the foot of a tree. In the Mahasiddhi stories preserved within the Tanrayana tradition - the realisation of the empty mind ground (or all-embracing void) renders the dichotomy between "ordained" and "laity" redundant. The Chinese-language Vinaya Discipline contains a clause which allows, under certain conditions, for an individual to self-perform an "Emergency" ordination. This is the case if the individual lives in isolation and has no access to the ordained Sangha or any other Buddhist Masters, etc. The idea is that should such expertise become available - then the ordination should be made official. However, the Vinaya Disciple in China states that a member of the ordained Sangha is defined in two-ways: 1) An individual who has taken both the Vinaya and Bodhisattva Vows - and has successfully completed all the required training therein. 2) Anyone who has realised "emptiness". Of course, in China all Buddhists - whether lay or ordained - are members of the (general) Sangha. The (general) Sangha, however, is led by the "ordained" Sangha. As lay-people (men, women, and children) can realise "emptiness" (enlightenment) - such an acommplished individual transitions (regardless of circustance) into the "ordained" Sangha. This is true even if such a person has never taken the Vinaya or Bodhisattva Vows - regardless of their lifestyle or position within society. Such an individual can be given a special permission to wear a robe in their daily lives - but these individuals do not have to agree with this. Realising "emptiness" is the key to this transformative process. Emptiness can be realised during seated meditation, during physical labour (or exercise), or during an enlightened dialogue with a Master. The first level is the "emptiness" realised when the mind is first "stilled". This "emptiness" is limited to just the interior of the head - but the ridge-pole of habitual ignorance has been permanently broken (this is the enlightenment of the Hinayana) - and is accompanied by a sense of tranquillity and bliss. This situstion (sat atop the hundred-foot pole) must be left behind. Through further training, the "bottom drops out the barrel" - and the perception of the mind expands throughout the ten directions. Emptiness embraces the mind, body, the surrounding environment - and all things within it.

0 Comments

Dear Gee

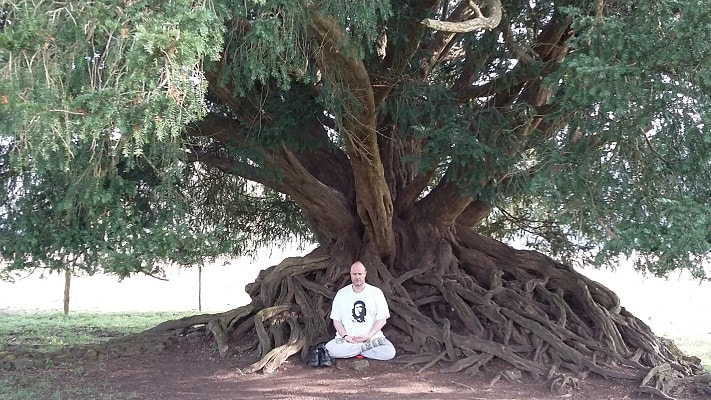

What is interesting is that after decades of effective inner and outer martial arts practice, I have arrived at a profound 'stable' state of mind, body and spirit (whatever that is). This journey has traversed many inner and outer levels or states of being. Mostly, this has included a logical approach to physical training motivated by 'doubt' a) in the process itself, and b) in my ability to keep-up the practice or c) to carry-out the prescribed practice correctly. This 'doubt' was inward whilst the physical 'outer' Chinese martial arts techniques were superb and highly effective. This 'doubt' (which ceased to function about 14-years-ago in c. 2007) acted like a force of magnetism drawing my 'uncertain' inner-being toward to the solid and stable outer-structure of the martial arts techniques and how they might be used in self-defence (function) and mind and body health and fitness (longevity). There is now a great awareness. A great all-embracing sense of psychological being that appears to be united with mind, body and environment. This unity I term 'spiritual' because all this seems 'transcendent'. Of course, whilst being driven on by the inner doubt to practice physical martial arts (as a form of 'armouring' against external attack), I also committed myself to intense Ch'an meditative practice as a means to 'uproot' this doubt which all motivating throughout my entire life to 'take action' in many different arenas - it also contained an element of 'weakness'. As I interpreted this 'weaknesses' as a major problem that a) held me back in a state of fearful 'non-action', or b) sabotaged physical actions so as to render all exertion completely pointless! The mind 'cleared' and 'expanded' - it became all-embracing so that the body stopped appearing to be 'outside' of it and took its place entirely within psychological awareness. Although I had my initial experiences of the realisation of a 'still' and 'empty' mind with its awareness expanding and embracing all things around 1990 - it took another 15-years for this experience to settle-down (2005), and about another two or three years for all vestiges of 'doubt' to completely dissolve (2007/8). What did happen around 1990, however, is that my physical use of outer Chinese martial arts technique deepened, expanded and matured, and since the time of 'teaching' in my own right (as opposed to 'training' under a teacher) - I have never lost a fight in the training hall. (Around a year before this experience, I was following a strict Chinese (Mahayana) Buddhist 'monastic' regime and sitting in meditation for hours a day practicing the hua tou 'Who is hearing?' Suddenly, whilst sitting in my 'cell' and without warning, my mind 'ceased to move' becomingly utterly and completely 'still'. This was accompanied by deep sense of permanent ecstasy! My Chinese teachers correctly taught me with 'silence' - whilst my Western teacher Richard Hunn (1949-2006) - my Western Ch'an teacher - correctly taught me with words! Ironically, he drew my attention to the authentic Chinese Ch'an texts. 'Neither be attached to the (realised) inner void - nor hindered by (the 'external') hindering phenomena'. It was deep within the 'silence' of my Chinese Ch'an Masters (including Chan Tin Sang [1924-1993] that I discovered the poignant meaning of Richard Hunn's spiritually 'vibrant' words. This is how I knew that Richard Hunn was correct in his understanding. Later, this dual instruction [into non-duality] led to the next shift in perspective This occurred a year later after a further period of intense practice, and was a product of a complete change or 'turning about' [see the 'Lankavatara Sutra'] at the deepest essence of the mind. It was such a profound and important 'first principle' that I nearly omitted it from the list of all the important events! I was once meditating sat on the ground outside 'returning' all sensory data 'back to its 'empty ground' essence - when a cool and refreshing Summer's freeze blew gently across my face. Suddenly, my mind instantaneously 'turned the right way around' immediately abandoning its previous 'inverted' functionality and appeared to 'expand', assume an 'all-embracing' position of being, whilst this 'new awareness' thoroughly permeated the physical-body and penetrated the physical universe throughout the past, present, and future! This permanent shift in psychological and physical manifestation changed 'me' from the DNA-chemical foundation upward and influenced all the views and opinions I now hold!) This includes not only transforming the experience of sparring with students (which is now unified experience premised upon wisdom, loving kindness and compassion) - but also manifested within the otherwise 'brutal' realm of 'honour fights' whereby unknown and unfamiliar individuals suddenly turn-up at my training hall and (disrespectfully) ask to spar! They wish to gain fame and fortune through 'out of control' violence which involves (for them) the 'beating' and 'exposing' a local (Chinese) gongfu teacher! How did this happen? I think whereas my opponents were still motivated by a deep and profound sense of 'doubt' (often involving a profound 'self-hatred') - I no longer experienced this 'doubt' which 'divides' human-beings during combat. Doubt by this time in my life had become nothing more than a profound sense of enhanced 'awareness' full of compassion and understanding. This is all held in place by a physical (martial) ability that can use 'gentleness' just as easily as 'harshness' to 'control' or 'regulate' physical interactions. Signed: Adrian Chan-Wyles [陳恒豫 - Chan Heng Yu] (22.11.2021) - '釋大道' (Shi Da Dao) Witnessed and Authenticated by Yau, Gee-Cheuk [邱芷芍] (22.11.2021) - 'Gee Wyles' - Wife of Adrian Chan-Wyles Author’s Note: In 2017, I wrote a short article about the Pali term ‘Bhavana’ and since then, I have been asked to write a more in-depth article regarding the meaning and application of this term in its Pali and Sanskrit context (both different and yet overlapping in places). Whereas in my earlier article (referenced below) I focused a great deal on the Chinese language term for ‘bhavana’ - in this outing I have limited myself to just the briefest of references to the Chinese equivalent – an act of considerable will-power considering Chinese Buddhism is one of my academic specialities (both ethnically and academically). However, I have always held the Theravada tradition in high regard and have been helped tremendously by its many practitioners and institutions around the world! From my Chinese Ch’an practice (and penetration of the empty mind ground) - I have come to see and appreciate how the many different branches of Buddhism (and reality in general) all manifest from the same stout trunk... Although what I convey to you is academically correct – you do not have to accept my conclusions. Always think for yourselves and make-up your own minds! ACW (17.9.2021) When I was studying Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka (in 1996), a term I came across continuously was ‘bhavana’ (‘भावना’ Pali and ‘भवन’ Sanskrit) - this was invariably used to refer to the act of seated ‘meditation’ and all the psychological and physical discipline required to successfully carry-out this important Buddhist practice. Indeed, within the Chinese written language, ‘bhavana’ is referred to as ‘修習’ (Xiu Xi) - or a central method of mind-body transformation – literally ‘self-cultivation method(s) or ‘habits’’ or ‘disciplined paths which intersect at a certain point of development’. A more succinct translation could be ‘paths of self-discipline' with the caveat that what is being suggested is the strict disciplining of the mind and body through the correct application of the Vinaya Discipline and the Bodhisattva Vows. Therefore, the single act of seated meditation has a wealth of supporting disciplinary activities surrounding its application, and does not appear does not suddenly appear out of a vacuum of non-effort. In other words, ‘bhavana’ refers to an act of ‘meditation’ which is the summation of the entire Buddhist path! Although the emphasis was always upon seated meditation, of course, standing, sitting and lying-down is allowed in the Buddhist Suttas – which very much depends upon the meditation teacher and the practitioner involved. Compassion, loving-kindness and wisdom must always be the driving force behind the practice of ‘bhavana’. As a ‘noun’, the Sanskrit dictionary states that भवन (bhavana) refers to:

The Pali dictionary suggests that ‘bhavana’ (भावना) refers to 'mental development' (lit. 'calling into existence, producing') in what in English is generally referred to 'meditation'. The Theravada School of Buddhism distinguishes two types of bhavana:

Interestingly, the very similar Sanskrit term ‘भावना’ (bhāvnā) refers to feeling, sensation, emotion and sentiment and is certainty moving toward the Buddhist (Pali) implications. Perhaps the Buddha modified a Pali term which once referred to the external practice of building houses and cultivating fields for farming – but changed its onus from this ‘objective’ meaning to a purely ‘subjective’ meaning relating to states of mind and patterns of thought and emotion. Just as rocks, weeds and stones are removed from the soil to make it fertile – the Buddhist practitioner uproots greed, hatred and delusion from the psychic fabric of the mind so that the mind becomes ‘fertile’ to receive the fruits of Buddhist self-cultivation. The Pali term appears to be referring to ‘that which arises from within’ - whilst the Sanskrit term is referring to ‘that which arises from without’. I would suggest that the inner perception of boundless space integrates with the awareness of boundless outer space – and that this is how the Buddha ultimately reconciles the two distinct meanings of this term. If a practitioner applies the Dhamma correctly – then like a plant growing from a seed into a might tree – the fruits of the Dhamma will manifest in the mind, body (and through behaviour) the environment!

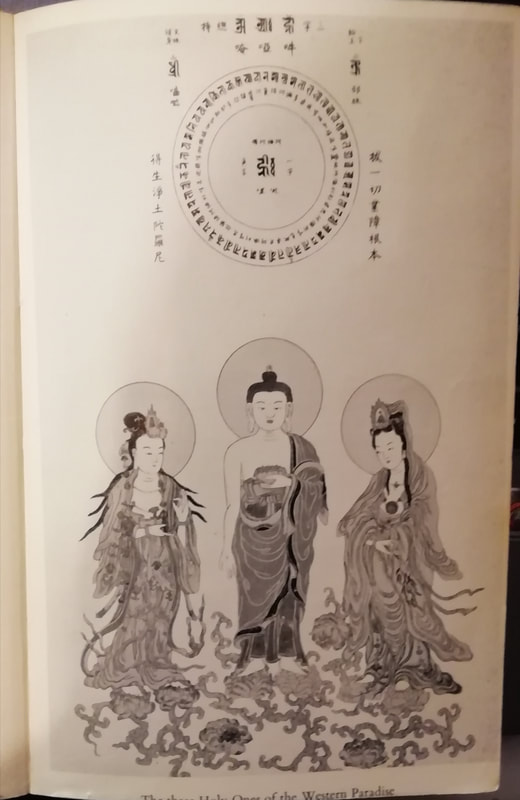

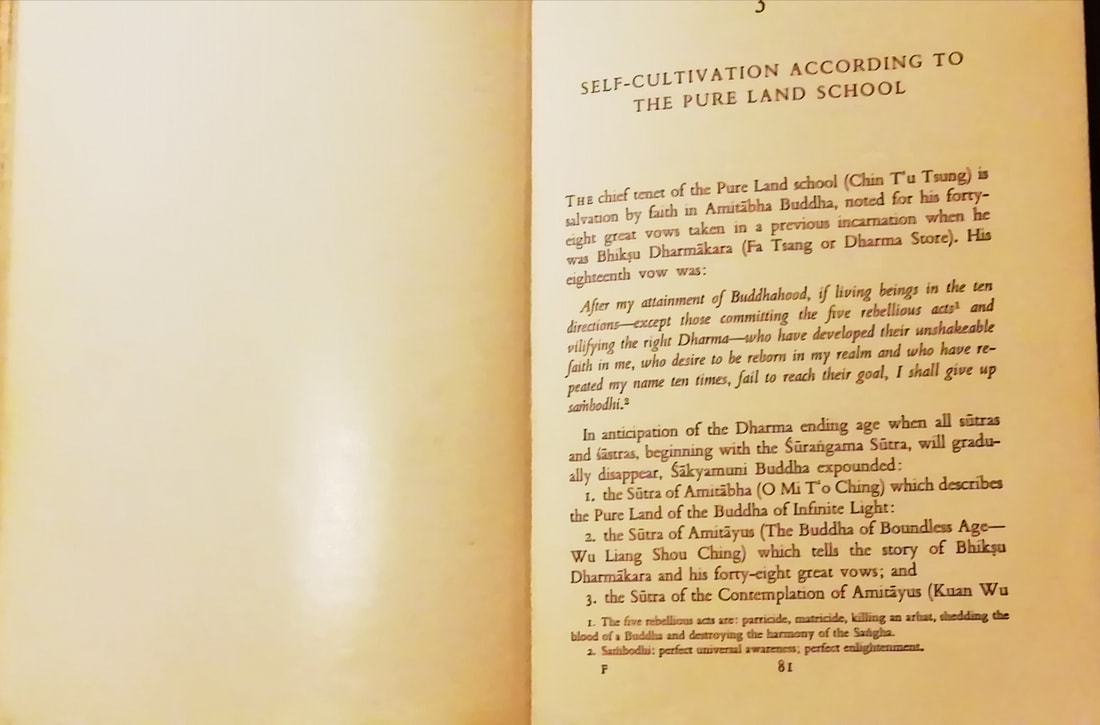

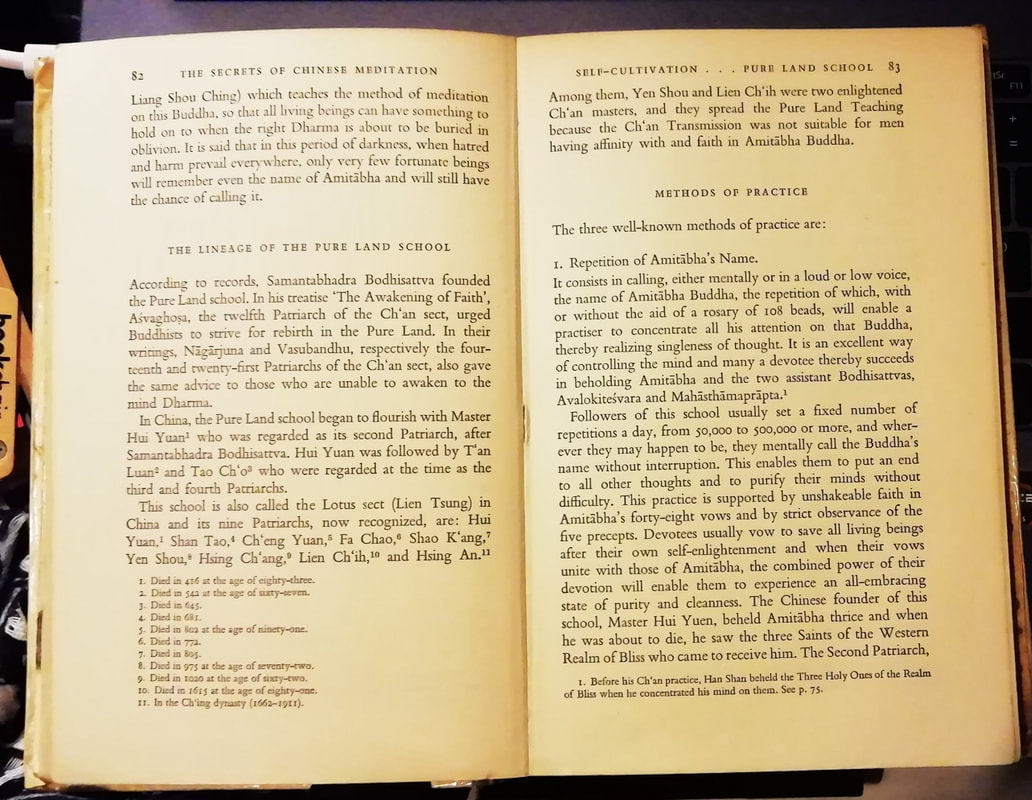

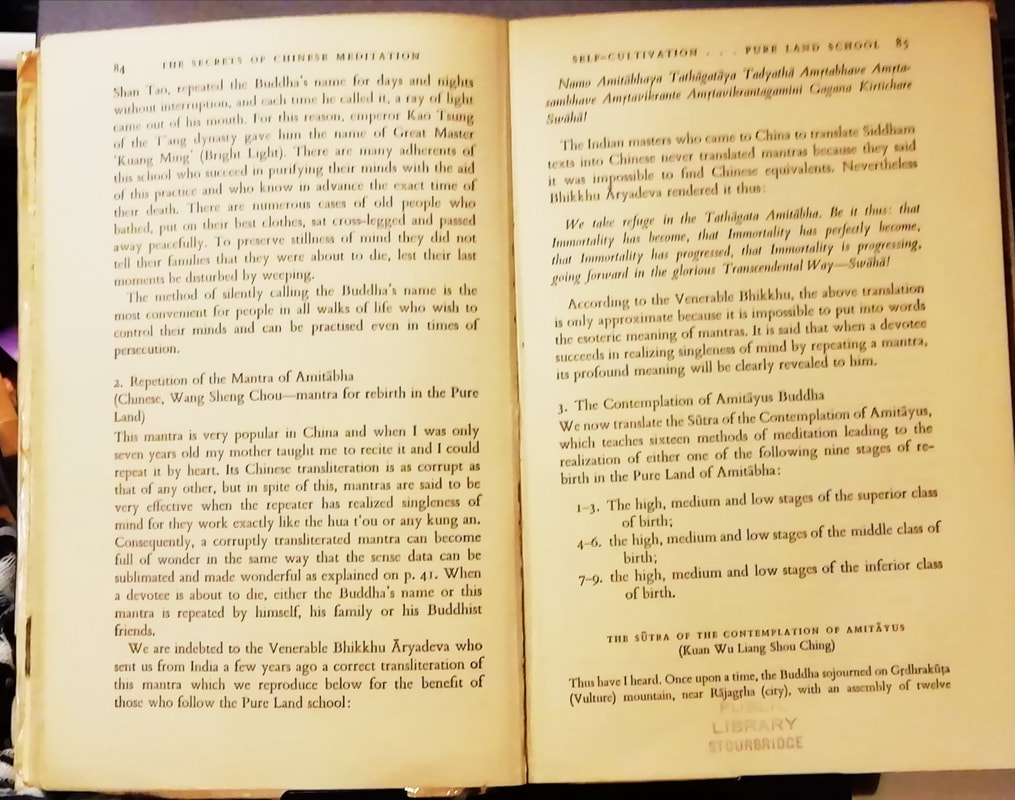

As a number of sincere practitioners have contacted me of late enquiring about the Pure Land Teachings as preserved within China - I have decided to make a simple offering of photographed pages presenting Charles Luk's expert guidance on this matter as recorded in his book entitled 'The Secrets of Chinese Meditation'. I have chosen the original (1964) hardback edition - as quite often later editions were sometimes altered here and there to suit the agenda of various publishers. This is Chapter Three (3) of that book which runs from and to pages 81=108.

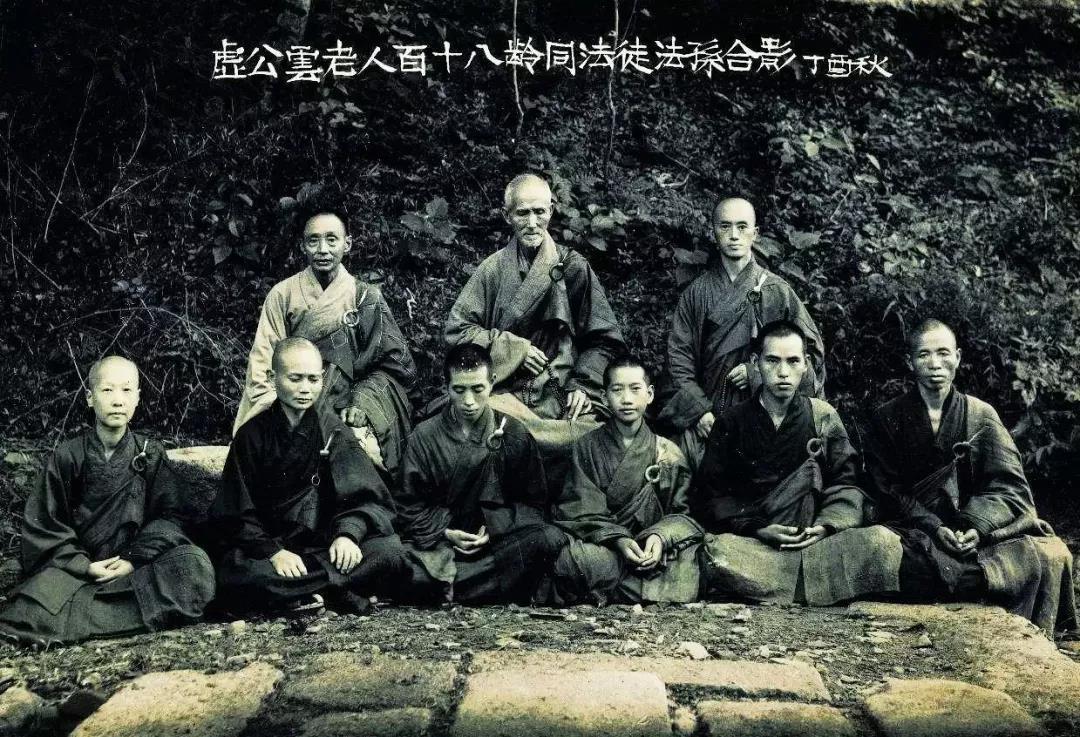

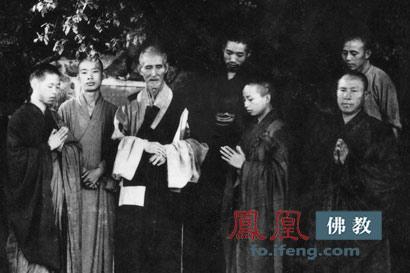

Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) was adamant that everyone follows the Vinaya Discipline. Of course, although the Buddhist monastics have to follow all the hundreds of rules – the laity have to follow fewer (minus the ‘celibacy’) rules – but those that are followed are still ‘Vinaya’ rules. This is as well as the Bodhisattva Vows - which monastics and laity generally follow (as they do not demand ‘celibacy’). Therefore, a firm ‘moral’ (Sila) base is established that limits bodily movements and assist in the ‘stilling’ of the mind. Buddhist morality advocates psychological and moral ‘non-attachment' to worldly sensation. This in-turn prevents a stimulation of the mind that generates and encourages greed, hatred and delusion. With the three-taints ‘cut-off’ - the practitioner can effectively focus all their efforts upon looking within and realising the empty mind ground. Furthermore, there is a belief within Buddhist culture that by following a morally pure existence an individual guarantees a good rebirth either as a human-being or in one of the divine ‘heavens’ reserved for people who have acquired very good karma but who are not yet enlightenment. Taking this model into account, a devout ‘Buddhist’ guarantees a future rebirth free of the suffering generally associated with the lower realms of demi-gods, spirits and hungry ghosts, etc. Simply following moral rules, however, does not guarantee enlightenment even if it does generate a morally pure behaviour and conduct. Unless a Buddhist practitioner ‘looks’ firmly and carefully into the interior of the mind – and perceives the empty mind ground – no mind-development can take place. This means that although following arbitrary rules of conduct creates pure karma – this process in and of itself does not break the practitioner ‘free’ of the ‘samsaric’ cycles within which humanity in trapped. Just as the moral force of good karma eventually runs-out – an individual is then propelled back into the lower realms of existence to start the process all over again. This means that ‘suffering’ is transformed in a number of ways – but is never transcended and overcome. The Buddha’s path requires that the ridge-pole of karmic ignorance is permanently ‘broken’ once and for all, and for this to happen, morally purifying action must be undertaken so that the Buddha’s meditational methods can be fully applied in an efficient manner. If a person immorally behaves in the world and reinforces greed, hatred and delusion, then no amount of meditation will ‘uproot’ the three-taints and ‘clear’ the surface mind. Indeed, in such a situation, meditation in such a situation might well have the effect of strengthening and magnifying the three-taints and making their presence ever more obvious and domineering! Precepts, therefore, only work if the attention of the mind is firmly ‘turned within’ so that the meditator can clearly perceive the underlying reality of the empty mind ground. This is the exercising of the ‘Mind Precept’ as taught by Master Xu Yun and which is part of the Caodong Ch’an tradition. This is clearly explained throughout the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra whilst never being mentioned by name. Unless the Buddhist method is being firmly applied to the mind – then all the precepts are relegated to ‘karma-purifiers’ and lose their enlightening function as ‘mind-realisers’. The hua tou and the gongan, for instance, are Ch’an methods for effectively ‘looking within’ - and it is through ‘looking within’ that the ‘Mind Precept’ is established. The empty mind ground is the essence of a) the mind and b) all phenomena. This means that all the hundreds of precepts of the Vinaya Discipline have the empty mind ground as their origination – with the understanding that this can only be known by ‘looking within’ and realising it as being so. By ‘looking within’ - the surface mind is ‘stilled’ and greed, hatred and delusion is fully and permanently ‘uprooted’. The emptiness of the mind eventually expands and becomes ‘all-embracing’ as it envelops all phenomena. This is how the ‘Mind Precept’ underlies all precepts and should serve as the foundation of genuine Buddhist self-discipline.

‘We are here to inquire into the hua-tou which is the way we should follow. Our purpose is to be clear about birth and death and to attain Buddhahood. In order to be clear about birth and death, we must have recourse to this hua-tou which should be used as the Vajra King’s precious sword to cut down demons if demons come and Buddha’s if Buddhas come so that no feelings will remain and not a single thing (Dharma) can be set up. In such a manner, where could there have been wrong thinking about writing poems and gathas and seeing such states as voidness and brightness? If you made your efforts so wrongly. I really do not know where your hua-tou went. Experienced Chan monks do not require further talks about this, but beginners should be very careful.’ Master Xu Yun (113-114 years-old) - Ch’an Week - 1953-1954 – Fourth Day - Jade Buddha Temple (Shanghai) Master Xu Yun never wastes a single word. This is because he is never confused as to the origin of a single thought. Master Xu Yun exists (psychologically and physically) within the permeant realisation of the empty mind ground. According to the historical (Indian) Buddha, ‘life’ as we experience it is unsatisfactory, seldom stable and prone to disappointment and ultimate dissolution. Physical life begins through the chemical explosion of conception, and ends when the body naturally shuts-down (during biological death), or is extinguished early through accident, illness or disaster, etc. Master Xu Yun lived through many such episodes throughout his extraordinarily long life (of two-cycles of the Chinese Zodiac). He lived within the space of the enlightened mind as explained in the Surangama Sutra. This is described as a round, all-embracing mirror that sees everything and rejects nothing. Like the sun – such a realised state shines on everything equally – bringing light and loving kindness to all phenomena whilst clearly distinguishing between this and that. This is why Master Xu Yun described the enlightened state as being ‘this and thus’ in his final years. What many believe to be exalted states experienced when training in methods of self-cultivation, are nothing more than marks of progression and subtle expressions of delusion that must be ruthlessly ‘cut-down’ without hesitation. Buddhas in the mind are only shadows in the imagination, nothing else. Being obsessed with a shadow is not the realisation of ‘enlightenment’ but just more delusion indulged in a more favourable direction. These achievements signify spiritual ‘dead-ends’ that many reach and mistake for the state of ultimate ‘enlightenment’. Practitioners then become satisfied to remain in these dark corners of the imagination and to lead all other into the same cul-de-sac of doom! When attachment mixes with a false attainment, then an individual will not be able to move-on for very long extended periods of time. All is lost as darkness replaces light – and ignorance dominates genuine wisdom. This quagmire can be avoided or escaped simple by applying the hua-tou correctly and effectively. What was once inevitable instantaneously ‘melts’ away as the hua-tou detaches the mind’s faulty awareness from this delusion and turns it toward the empty mind ground. This demonstrates the power of a) delusions to fool and distract the mind, and b) for the hua-tou method to quickly resolve this issue. The hua-tou is a very effective method of self-cultivation now only found in the Chinese Ch’an School of Buddhism (and the various lineages that have spread to other countries). Looking within is a matter of proper view – nothing else. Looking correctly will reveal the empty mind ground – looking incorrectly will reveal the delusion of the mind which cannot be escaped. Settling the body and directing the awareness is more important than all the passing phenomena of the external world (good or bad) - and has nothing to do with existential circumstance. This is why Ch’an is both difficult and easy.

Avoiding the Ten Evil Acts (Dasa Akusala)

A) The Three Evil Acts Associated with the Bodily-Action: 1) Killing 2) Stealing 3) Adultery B) The Four Evil Acts Associated with Speech: 4) Lying 5) Slander 6) Harsh Words 7) Profitless Talk C) The Three Evil Acts Associated with the Mind: 8) Greed 9) Hatred 10) Delusion As Buddhism is a Form of Mental Hygiene – the Following Must Be Uprooted through Meditation: 1) Greed (Abhijjha), 2) Hatred (Vyapada), 3) Ill-Will (Kodha), 4) Enmity (Upanaha), 5) Belittling (Makkha), 6) Pretension (Palasa), 7) Envy (Issa), 8) Jealously (Macchariya), 9) Hypocrisy (Maya), 10) Craftiness (Satheyya), 11) Obduracy (Thambha), 12) Vieing (Sarambha), 13) Conceit (Mana), 14) Haughtiness (Atimana), 15) Infatuation (Mada), and 16) Unheedfulness (Pamada). As these ‘darken the mind’ they must be ‘uprooted’. Ten Moral Acts (Dasa Kusala) 1) Giving (Dana), 2) Moral Conduct (Sila), Meditation (Bhavana), 4) Respecting the Worthy (Apacayana), 5) Ministering to the Worthy (Veyvavacca), 6) Offering Merit (Pattidana), 7) Partakingbof Merit (Pattanumodana), 8) Hearing the Teaching (Dhammasavana), 9) Teaching the Dhamma (Dhamma Desana) and 10) Rectification of False Views (Ditthijjukamma). The reality of living in the material world is entirely a matter of casual circumstance. Most people make their way through life in any way they can, regardless of the inherent conditions (good, neutral or bad, etc). The Ch’an masters in the old days were very strict and did not care whatsoever about casual circumstance. Their main emphasis was only to direct the attention ‘inward’ so that the empty mind ground can be fully cognised and integrated with. There is no gossip or discussion tolerated about the nature of the times, with only ‘looking within’ viewed as a valid approach to existence. The Ch’an masters advised that we must ‘adjust ourselves to circumstance’, whilst the mind is turned inward and the interior of conscious awareness illuminated through continuous concentration. This is the essence of the Buddha’s method. Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) lived an extraordinary life and was involved in very important times in historical development, but he was continuously ‘indifferent’ to what was happening around him, whilst taking every ‘correct’ action that was required at the time. Looking within with strength and purpose is not a denial of material reality, but is the acknowledgement of the Buddha’s method. The Ch’an method is nothing but the direct realisation of the empty mind ground so that it becomes the place of permanent abode – an abode which generates loving-kindness, compassion and wisdom! |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed