|

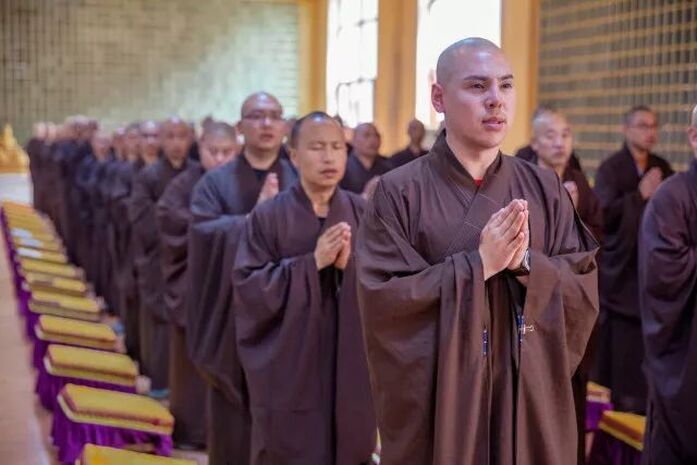

Buddhist monasticism is flexible. Although it is correct to assume that it is usually necessary for an individual to undergo a period of isolatory training (to establish and stabilise the realisation of the void) - it is also true that compassionate (Bodhisattva) activity must also be pursued throughout the myriad conditions that define worldly existence. This is true of all Buddhist traditions - as even the Bhikkhus of the Theravada School must "walk" (in a self-aware manner) through the surrounding (lay) villages - begging for food on a daily basis. Living a hermitic or cloistered existence is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Of course, this period may be repeated more than once and last any length of time. When entering different situations - the Bodhisattva does not lose sight of the realised void regardless of the external conditions experienced. The Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) spent around 15 years living with bandits and barbarians in the hills - retaining a vegetarian diet - even though he was not yet formally ordained in the Sangha. Within China, the Mahayana Bhikshu must take the hundreds of Vinaya Discipline Vows as well as the parallel Bodhisattva Vows (the former requires complete celibacy whilst the latter requires moral discipline but not celibacy). Anyone can be a "Bodhisattva" - whilst a formal Buddhist monastic must adhere to the discipline of the Vinaya Discipline. A lay Buddhist person also adheres to the Vinaya Discipline - but only upholds the first Five, Eight or Ten vows, etc. Vimalakirti is an example of an Enlightened Layperson whose wisdom was complete and superior to those who were still wrapped in robes and sat at the foot of a tree. In the Mahasiddhi stories preserved within the Tanrayana tradition - the realisation of the empty mind ground (or all-embracing void) renders the dichotomy between "ordained" and "laity" redundant. The Chinese-language Vinaya Discipline contains a clause which allows, under certain conditions, for an individual to self-perform an "Emergency" ordination. This is the case if the individual lives in isolation and has no access to the ordained Sangha or any other Buddhist Masters, etc. The idea is that should such expertise become available - then the ordination should be made official. However, the Vinaya Disciple in China states that a member of the ordained Sangha is defined in two-ways: 1) An individual who has taken both the Vinaya and Bodhisattva Vows - and has successfully completed all the required training therein. 2) Anyone who has realised "emptiness". Of course, in China all Buddhists - whether lay or ordained - are members of the (general) Sangha. The (general) Sangha, however, is led by the "ordained" Sangha. As lay-people (men, women, and children) can realise "emptiness" (enlightenment) - such an acommplished individual transitions (regardless of circustance) into the "ordained" Sangha. This is true even if such a person has never taken the Vinaya or Bodhisattva Vows - regardless of their lifestyle or position within society. Such an individual can be given a special permission to wear a robe in their daily lives - but these individuals do not have to agree with this. Realising "emptiness" is the key to this transformative process. Emptiness can be realised during seated meditation, during physical labour (or exercise), or during an enlightened dialogue with a Master. The first level is the "emptiness" realised when the mind is first "stilled". This "emptiness" is limited to just the interior of the head - but the ridge-pole of habitual ignorance has been permanently broken (this is the enlightenment of the Hinayana) - and is accompanied by a sense of tranquillity and bliss. This situstion (sat atop the hundred-foot pole) must be left behind. Through further training, the "bottom drops out the barrel" - and the perception of the mind expands throughout the ten directions. Emptiness embraces the mind, body, the surrounding environment - and all things within it.

0 Comments

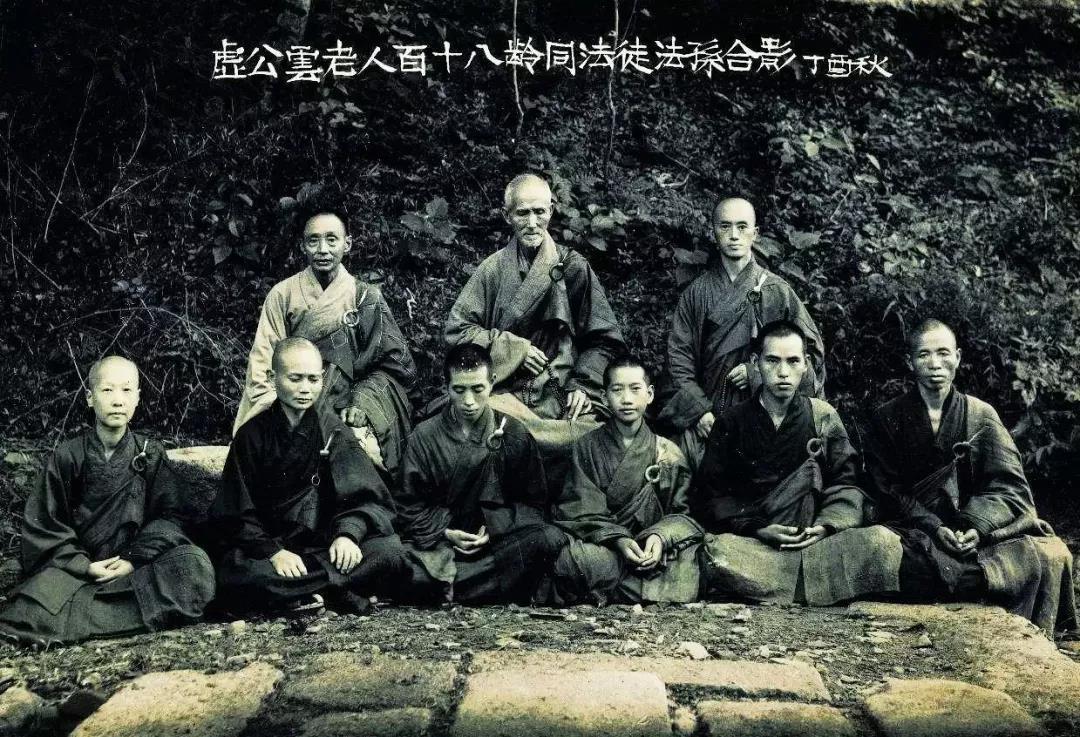

Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) was adamant that everyone follows the Vinaya Discipline. Of course, although the Buddhist monastics have to follow all the hundreds of rules – the laity have to follow fewer (minus the ‘celibacy’) rules – but those that are followed are still ‘Vinaya’ rules. This is as well as the Bodhisattva Vows - which monastics and laity generally follow (as they do not demand ‘celibacy’). Therefore, a firm ‘moral’ (Sila) base is established that limits bodily movements and assist in the ‘stilling’ of the mind. Buddhist morality advocates psychological and moral ‘non-attachment' to worldly sensation. This in-turn prevents a stimulation of the mind that generates and encourages greed, hatred and delusion. With the three-taints ‘cut-off’ - the practitioner can effectively focus all their efforts upon looking within and realising the empty mind ground. Furthermore, there is a belief within Buddhist culture that by following a morally pure existence an individual guarantees a good rebirth either as a human-being or in one of the divine ‘heavens’ reserved for people who have acquired very good karma but who are not yet enlightenment. Taking this model into account, a devout ‘Buddhist’ guarantees a future rebirth free of the suffering generally associated with the lower realms of demi-gods, spirits and hungry ghosts, etc. Simply following moral rules, however, does not guarantee enlightenment even if it does generate a morally pure behaviour and conduct. Unless a Buddhist practitioner ‘looks’ firmly and carefully into the interior of the mind – and perceives the empty mind ground – no mind-development can take place. This means that although following arbitrary rules of conduct creates pure karma – this process in and of itself does not break the practitioner ‘free’ of the ‘samsaric’ cycles within which humanity in trapped. Just as the moral force of good karma eventually runs-out – an individual is then propelled back into the lower realms of existence to start the process all over again. This means that ‘suffering’ is transformed in a number of ways – but is never transcended and overcome. The Buddha’s path requires that the ridge-pole of karmic ignorance is permanently ‘broken’ once and for all, and for this to happen, morally purifying action must be undertaken so that the Buddha’s meditational methods can be fully applied in an efficient manner. If a person immorally behaves in the world and reinforces greed, hatred and delusion, then no amount of meditation will ‘uproot’ the three-taints and ‘clear’ the surface mind. Indeed, in such a situation, meditation in such a situation might well have the effect of strengthening and magnifying the three-taints and making their presence ever more obvious and domineering! Precepts, therefore, only work if the attention of the mind is firmly ‘turned within’ so that the meditator can clearly perceive the underlying reality of the empty mind ground. This is the exercising of the ‘Mind Precept’ as taught by Master Xu Yun and which is part of the Caodong Ch’an tradition. This is clearly explained throughout the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra whilst never being mentioned by name. Unless the Buddhist method is being firmly applied to the mind – then all the precepts are relegated to ‘karma-purifiers’ and lose their enlightening function as ‘mind-realisers’. The hua tou and the gongan, for instance, are Ch’an methods for effectively ‘looking within’ - and it is through ‘looking within’ that the ‘Mind Precept’ is established. The empty mind ground is the essence of a) the mind and b) all phenomena. This means that all the hundreds of precepts of the Vinaya Discipline have the empty mind ground as their origination – with the understanding that this can only be known by ‘looking within’ and realising it as being so. By ‘looking within’ - the surface mind is ‘stilled’ and greed, hatred and delusion is fully and permanently ‘uprooted’. The emptiness of the mind eventually expands and becomes ‘all-embracing’ as it envelops all phenomena. This is how the ‘Mind Precept’ underlies all precepts and should serve as the foundation of genuine Buddhist self-discipline.

Many people are surprised to learn that Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) was subject to a more or less continuous stream of allegations claiming that he routinely ‘broke’ the Vinaya Discipline and the Bodhisattva Vows. These assertions were usually made by common people with an axe to grind for some reason or other. The fact that no one took these allegations seriously is simply because no one who mattered believed any of it to be true. Master Xu Yun was accused of seducing young girls and women, as well as pursuing homosexual relationships with young monks. When these reports were found to be groundless – Master Xu Yun was accused of amassing money and using it to lead a life of luxury and leisure! Again, no evidence was ever found and so these allegations were ignored like all the others. When he was married (in his late teens) Master Xu Yun never touched his two wives. Years later, this was confirmed by these (now elderly) ladies who had become ordained Buddhist nuns after their husband left to become a monk around 1858. These ladies were virginal when they entered the Buddhist nunnery. My personal experience of Chinese monastic communities, as well as from the memories of other Western people who also lived as a Buddhist monk in China, confirm that homosexuality (as well as any type of sexual expression) was not present. This is because the facility of human desire is ‘turned inward’ and transmutated into pure spiritual light and energy that emanates from the centre of the forehead and from there permeates the entire body and environment. This process detaches sexual energy from the sexual organs and diverts the imagination of the mind away from sexual fulfilment through the sexual organ, focusing on ‘returning’ all this sensation back toward the empty mind ground. There is no outward sexual reaction or perversion within the average Chinese Ch’an monastery because the subject-object dichotomy that drives the sexual drive within delusive society no longer exists. There is a point in this process where the sexual drive is transformed forever regardless of circumstance. Although a conducive environment is beneficially to start with, eventually, once the six senses are permanently ‘purified’ and ‘cleansed’, then a lay-men such as Vimalakirti and Hui Neng (prior to the latter’s eventual ordination) where able to live within ordinary society and yet never break their Vinaya Discipline. Vimalakirti had a number of wives and numerous children – and yet the Buddha stated that he ‘never’ broke the vow of celibacy. Vimalakirti also criticised the Buddha’s ordained disciple Upali (a Master of the Vinaya Disciple) for being attached (in the wrong) way to the ‘letter of the law’. Vimalakirti stated that being ‘attached’ to celibacy in such a one-sided manner was as bad as being mindlessly attached to sexual pleasure! The answer is that ‘pleasure’, ‘pain’ and ‘neutrality’ are all perceived to be equally ‘empty’ of any and all permanent reality. All emerge from the empty mind ground as karmic attributes that simply take the form that is implicitly conditioned within each strand of expression. This Mahayana penetrating of all phenomena is very different to Upali’s Hinayana notion of just avoiding ‘pleasure’, etc. It is the same for ‘praise’ and ‘blame’, as both are equally ‘empty’ of any intrinsic or separate value. A practitioner who has penetrated the empty mind ground exists in a permanent state of divine indifference and are unmoved by either praise or blame. Reacting to the ignorance of others with the same ignorance does not happen because it cannot happen. Once the empty mind ground has been permanently penetrated, understood and integrated with, then there is never any slipping back to a more deficient position of understanding. People who operate through the ego are continuously attempting to make some kind of social gain through manipulating those around them. A Ch’an Master sees this straightaway and reveals the underlying reality of those who approach with ulterior motives. All is wisdom, loving kindness and compassion.

A ‘Personal’, or ‘mind to mind’ transmission is described as follows. Enlightenment is the realisation of the empty mind ground (relative enlightenment) - and the integration of this realisation of with all phenomena (full enlightenment). An enlightened being (or ‘Bodhisattva’) is neither attached to the void or hindered by phenomena – a reality that ‘deepens’ in maturity as the years go by. Transmission is the recognition by an enlightened master that a disciple has realised this state, and is therefore able (and ‘authorised’) to teach others to realise this state. A ‘Supportive’ transmission, by way of contrast, is designed to ‘assist’ and ‘uplift’ a practitioner in preparation for the achievement of ‘relative’ and ‘full’ enlightenment, and to transition into a ‘Personal’ transmission should an individual achieve a suitable status of realisation. Master Han Shan Deqing [憨山德清] (1545-1623) may be taken as a reliable model of a Ch’an monk who realised full self-enlightenment (confirmed through the guidance found in the Surangama Sutra). Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) inherited the Dharma-Name ‘Deqing’ (德清) - or ‘Virtuous Clarity’. Master Han Shan understood that ‘sound’ was only perceptible through a ‘subject’ - ‘object’ duality when the mind ‘moved’. When the mind was ‘stilled’, all perception came to an end for the realisation of ‘relative’ enlightenment’. From this position, and following a period of further training, Han Shan’s mind appeared to ‘expand’ and embrace the entire environment (full enlightenment) - a luminous state within which the mind becomes like a mirror and reflects all things. Another text designed to assist the self-enlightenment process is the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra – within which the enlightened layman – Vimalakirti - ‘corrects’ the Buddha’s monastic disciples who have only realised the state of ‘relative’ enlightenment. Through his ‘supportive’ presence and influence he provides the outer and inner conditions (and expert stimulus) to ‘assist’ these monks to ‘move beyond’ their own limited achievements. Vimialakirti’s example is the ‘essence’ of the Guild of Hui Neng’s ongoing Cao Dong transmission. ACW (5.10.2020)

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed