|

Buddhist monasticism is flexible. Although it is correct to assume that it is usually necessary for an individual to undergo a period of isolatory training (to establish and stabilise the realisation of the void) - it is also true that compassionate (Bodhisattva) activity must also be pursued throughout the myriad conditions that define worldly existence. This is true of all Buddhist traditions - as even the Bhikkhus of the Theravada School must "walk" (in a self-aware manner) through the surrounding (lay) villages - begging for food on a daily basis. Living a hermitic or cloistered existence is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Of course, this period may be repeated more than once and last any length of time. When entering different situations - the Bodhisattva does not lose sight of the realised void regardless of the external conditions experienced. The Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) spent around 15 years living with bandits and barbarians in the hills - retaining a vegetarian diet - even though he was not yet formally ordained in the Sangha. Within China, the Mahayana Bhikshu must take the hundreds of Vinaya Discipline Vows as well as the parallel Bodhisattva Vows (the former requires complete celibacy whilst the latter requires moral discipline but not celibacy). Anyone can be a "Bodhisattva" - whilst a formal Buddhist monastic must adhere to the discipline of the Vinaya Discipline. A lay Buddhist person also adheres to the Vinaya Discipline - but only upholds the first Five, Eight or Ten vows, etc. Vimalakirti is an example of an Enlightened Layperson whose wisdom was complete and superior to those who were still wrapped in robes and sat at the foot of a tree. In the Mahasiddhi stories preserved within the Tanrayana tradition - the realisation of the empty mind ground (or all-embracing void) renders the dichotomy between "ordained" and "laity" redundant. The Chinese-language Vinaya Discipline contains a clause which allows, under certain conditions, for an individual to self-perform an "Emergency" ordination. This is the case if the individual lives in isolation and has no access to the ordained Sangha or any other Buddhist Masters, etc. The idea is that should such expertise become available - then the ordination should be made official. However, the Vinaya Disciple in China states that a member of the ordained Sangha is defined in two-ways: 1) An individual who has taken both the Vinaya and Bodhisattva Vows - and has successfully completed all the required training therein. 2) Anyone who has realised "emptiness". Of course, in China all Buddhists - whether lay or ordained - are members of the (general) Sangha. The (general) Sangha, however, is led by the "ordained" Sangha. As lay-people (men, women, and children) can realise "emptiness" (enlightenment) - such an acommplished individual transitions (regardless of circustance) into the "ordained" Sangha. This is true even if such a person has never taken the Vinaya or Bodhisattva Vows - regardless of their lifestyle or position within society. Such an individual can be given a special permission to wear a robe in their daily lives - but these individuals do not have to agree with this. Realising "emptiness" is the key to this transformative process. Emptiness can be realised during seated meditation, during physical labour (or exercise), or during an enlightened dialogue with a Master. The first level is the "emptiness" realised when the mind is first "stilled". This "emptiness" is limited to just the interior of the head - but the ridge-pole of habitual ignorance has been permanently broken (this is the enlightenment of the Hinayana) - and is accompanied by a sense of tranquillity and bliss. This situstion (sat atop the hundred-foot pole) must be left behind. Through further training, the "bottom drops out the barrel" - and the perception of the mind expands throughout the ten directions. Emptiness embraces the mind, body, the surrounding environment - and all things within it.

0 Comments

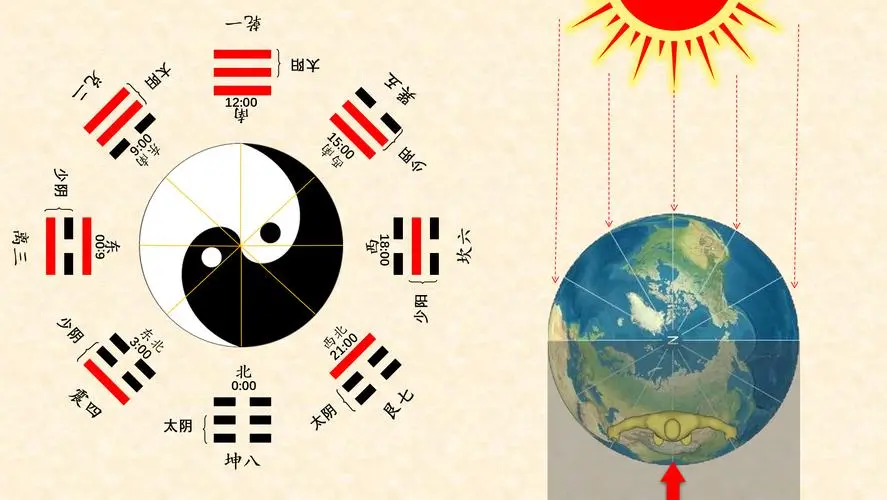

Dear B It is interesting that those who were illiterate - such as Hui Neng - could have the essence of mind development conveyed to them by simply studying the "shape" (form) of the Trigrams and Hexagrams. Of course, Master Cao develops this idea through his shaded roundels. Indeed, it could well be that the roundels of the Caodong School eventually led to the development of the Taiji Tu [太極圖] (Yin-Yang Symbol) that was developed during the latter Song Dynasty. Either way - the "beyond words" teaching - may have had its root in illiteracy - as the historical Buddha could not read or write - as astonishing as that seems!

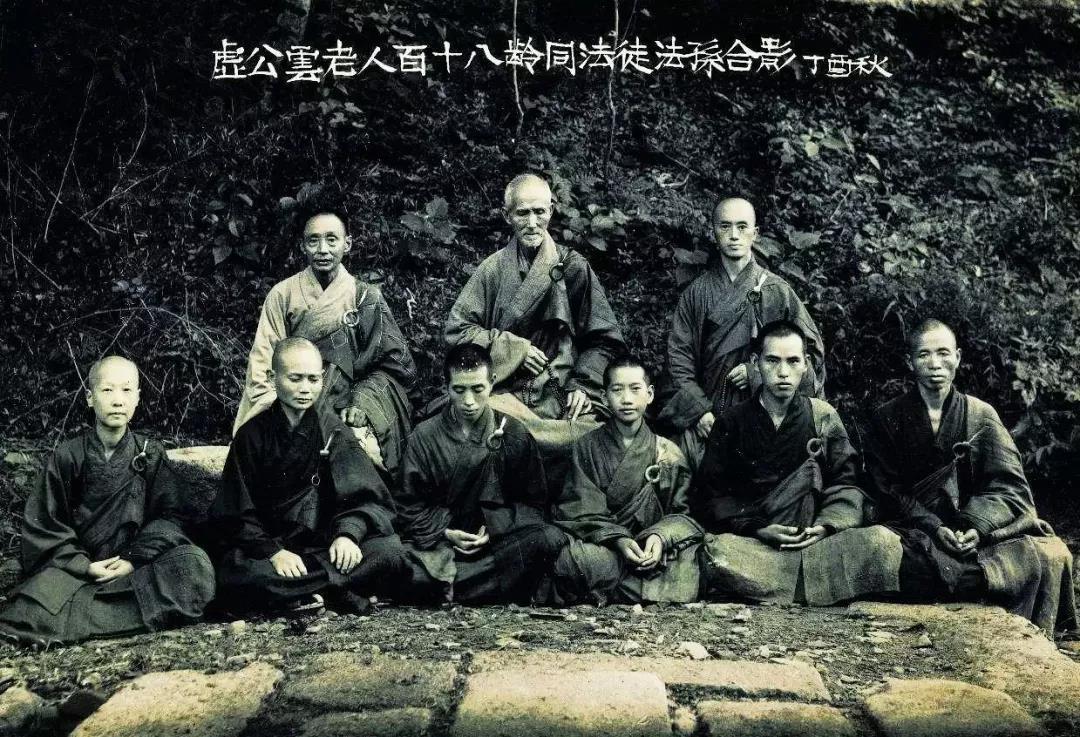

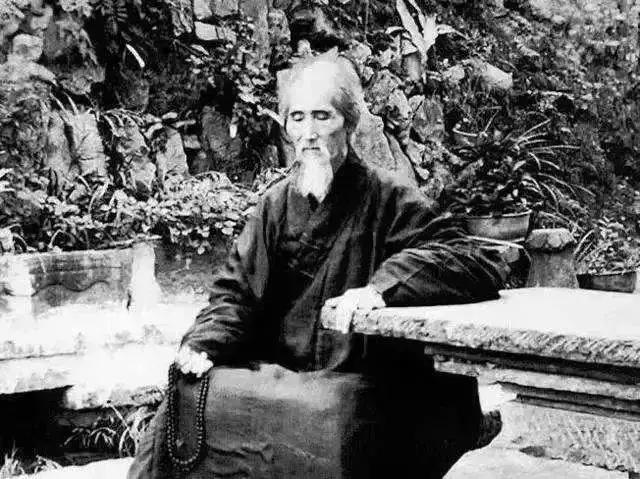

Many people are surprised to learn that Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) was subject to a more or less continuous stream of allegations claiming that he routinely ‘broke’ the Vinaya Discipline and the Bodhisattva Vows. These assertions were usually made by common people with an axe to grind for some reason or other. The fact that no one took these allegations seriously is simply because no one who mattered believed any of it to be true. Master Xu Yun was accused of seducing young girls and women, as well as pursuing homosexual relationships with young monks. When these reports were found to be groundless – Master Xu Yun was accused of amassing money and using it to lead a life of luxury and leisure! Again, no evidence was ever found and so these allegations were ignored like all the others. When he was married (in his late teens) Master Xu Yun never touched his two wives. Years later, this was confirmed by these (now elderly) ladies who had become ordained Buddhist nuns after their husband left to become a monk around 1858. These ladies were virginal when they entered the Buddhist nunnery. My personal experience of Chinese monastic communities, as well as from the memories of other Western people who also lived as a Buddhist monk in China, confirm that homosexuality (as well as any type of sexual expression) was not present. This is because the facility of human desire is ‘turned inward’ and transmutated into pure spiritual light and energy that emanates from the centre of the forehead and from there permeates the entire body and environment. This process detaches sexual energy from the sexual organs and diverts the imagination of the mind away from sexual fulfilment through the sexual organ, focusing on ‘returning’ all this sensation back toward the empty mind ground. There is no outward sexual reaction or perversion within the average Chinese Ch’an monastery because the subject-object dichotomy that drives the sexual drive within delusive society no longer exists. There is a point in this process where the sexual drive is transformed forever regardless of circumstance. Although a conducive environment is beneficially to start with, eventually, once the six senses are permanently ‘purified’ and ‘cleansed’, then a lay-men such as Vimalakirti and Hui Neng (prior to the latter’s eventual ordination) where able to live within ordinary society and yet never break their Vinaya Discipline. Vimalakirti had a number of wives and numerous children – and yet the Buddha stated that he ‘never’ broke the vow of celibacy. Vimalakirti also criticised the Buddha’s ordained disciple Upali (a Master of the Vinaya Disciple) for being attached (in the wrong) way to the ‘letter of the law’. Vimalakirti stated that being ‘attached’ to celibacy in such a one-sided manner was as bad as being mindlessly attached to sexual pleasure! The answer is that ‘pleasure’, ‘pain’ and ‘neutrality’ are all perceived to be equally ‘empty’ of any and all permanent reality. All emerge from the empty mind ground as karmic attributes that simply take the form that is implicitly conditioned within each strand of expression. This Mahayana penetrating of all phenomena is very different to Upali’s Hinayana notion of just avoiding ‘pleasure’, etc. It is the same for ‘praise’ and ‘blame’, as both are equally ‘empty’ of any intrinsic or separate value. A practitioner who has penetrated the empty mind ground exists in a permanent state of divine indifference and are unmoved by either praise or blame. Reacting to the ignorance of others with the same ignorance does not happen because it cannot happen. Once the empty mind ground has been permanently penetrated, understood and integrated with, then there is never any slipping back to a more deficient position of understanding. People who operate through the ego are continuously attempting to make some kind of social gain through manipulating those around them. A Ch’an Master sees this straightaway and reveals the underlying reality of those who approach with ulterior motives. All is wisdom, loving kindness and compassion.

Chinese Ch’an is beyond words and sentences. Of this, we can all agree. However, I have just made use of ‘words and sentences’ to convey an entire list of concepts, albeit in an efficient use of language. The point is that each word (spelt correctly) is used like an arrow ‘shooting’ toward the target. Nothing can stop it, and its direct is clear. A Ch’an teacher knows ‘exactly’ where the target is and ‘how’ it must be reached. Enquirers are not clear where the target is, or how they are to reach it. The interaction between ‘teacher’ and ‘enquirer’ is one of directing the arrow toward the target. Or, to explain it another way, the teacher ensures that the target is in the right place when the enquirer releases the arrow toward it! Two people, one arrow and a single target. Depending upon what is required, the Ch’an teacher either adjusts the direction of the arrow, or alters the position of the target. Once the two are ‘connected’ as ‘one’ - then the method for achieving contact immediately becomes irrelevant as the arrow no longer requires adjusting or the target moving. Language is important as a means to convey understanding and context, but the torrent of words create a cascade of meaning that never ends – even though each word contains only a limited over-all meaning. Language is accumulative. Meaning and understanding is accrued over-time – and yet sometimes the deliberate ‘non-use’ of language can be an important lever in the process of re-aligning meaning, reason, logic and understanding. A Ch’an teacher can deploy words and sentences with the thunder of an avalanche – or the gentleness of a quiet cave interior. Both may appear to be a little frightening and intimidating – but both have their developmental purpose. The hua tou deals exclusively with words. Actually, it deals specifically with the ‘origin’, ‘manifestation’ and ‘dissipation’ of each word as it emerges from the empty mind ground, becomes fully ‘established’ in the mind as a thought, and then ‘dissolves’ back into nothing. If a Ch’an practitioner studies the hua tou for years on end, he or she is studying the essence of all literature as it arises in the mind! This worked for the Sixth Patriarch – Hui Neng – who was illiterate when he first realised enlightenment. Although he could not read or write (a common experience for around 90% of Chinese people living within feudal China), nevertheless, if a text was read to him, he could fully explain its deep and profound meaning!

Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) inherited all Five Ch’an School in China. Although Japanese and US scholarship often claim that Chinese Buddhism ‘died-out’ - and was re-imported from Japan – this is untrue and a product of bias and incomplete knowledge. Certainly, Master Xu Yun would not have agreed with this assumption. All the lineages of Chinese Buddhism have continued to survive through thick and thin as the forces of Chinese history have ebbed and flowed. When conditions are appropriate, the various lineages have become ‘public’, popular and well-known, but when conditions have changed, then these lineages have withdrawn into the background and become ‘private’ transmissions away from the public gaze. Regardless of whether a lineage was ‘private’ or ‘public’ - Master Xu Yun was sought-out to carry the Dharma forward – such was the purity of his being. He lived for two full cycles of the Chinese Zodiac (60-years X 2) because of his shining virtue. He inherited and passed-on many lineages of Buddhism – far more than within the Ch’an School – but his personal lineage was that of the Cao Dong School. This is the lineage he personally inherited from Master Miao Lian (1824-1907) and the lineage he was instructed to personally transmit to a special ‘inner’ lineage of lay and monastic practitioners. The Cao Dong lineage was the path that he personally preferred amongst all the others that he was an expert in understanding and teaching. The robe of the Cao Dong School is ‘black’ and on special occasions Master Xu Yun would swap his patch-work robe for the his carefully looked-after Cao Dong robe (pictured above). Master Caoshan (840-901) - the disciple of Master Dongshan (807–869) [the Founder of the ‘Cao Dong’ School] - visited the Temple of the Sixth Patriarch Hui Neng situated in the Caoxi area of Guangdong province (in Southern China). He then re-named the mountain he settled on (in the Fuzhou area of Fujian province) as ‘Caoshan’ in honour of the memory of Master Hui Neng. This is because the Cao Dong lineage flows all the way back to Hui Neng and is directly linked to his body which still sits upright in meditation in China today. ALL advanced Cao Dong must master the ability of passing from this life in the manner of Hui Neng. A monk asked Master Dongshan: “The Venerable Sir is unwell but is there anyone who is never ill?” The master replied: “Yes, there is.” The monk asked: “Does the one who is never ill still look at you?” The master replied: “(On the contrary,) the lot falls on this old monk to look at him.” The monk asked: “How does the Venerable Master look at him?” The master replied: “When the old monk looks at him, he does not see any illness.” The master then asked the monk: “When you leave this leaking shell, where will you go to meet me?” The monk could not reply... After saying this, he ordered his head to be shaved and (his body) bathed, after which he put on a robe and struck the bell to bid farewell to the community. As he sat down and passed away, the monks wept sadly without interruption. Suddenly, he opened his eyes and said: “Leavers of homes should be mindless of externals; this is true practice. What is the use of being anxious for life and death?” The master then ordered a stupidity-purifying mal and seeing that his disciples were strongly attached to him, he postponed (his death) for seven days. (On the last day,) he entered the dining hall behind his disciples and after taking food, said: “I am all right; when I am about to leave, you should all keep quiet.” Then he returned to the abbot’s room where sat cross-legged and passed away. A monk asked the Master Caoshan: “Every part of my body is sick; will you please cure me?” The master replied: “I will not.” The monk asked: “Why not?” The master replied: “It is impossible to teach you how to live and die.” The monk asked: “Does the master not have great compassion (for other people)?” The master replied: “Yes, he has.” The monk asked: “What should one do when all the six robbers come suddenly? The master replied: “One should also have great compassion.” The monk asked: “How to have a great compassion?” The master replied: “All should be cut down at one stroke by the sword.” The monk asked: “What next after (the sword has) cut them all down?” The master replied: “The realisation of sameness will then be realised.” After saying this, he burned incense sticks, sat (cross-legged) and passed away in his sixty-second year and at his dharma-age of thirty-seven.

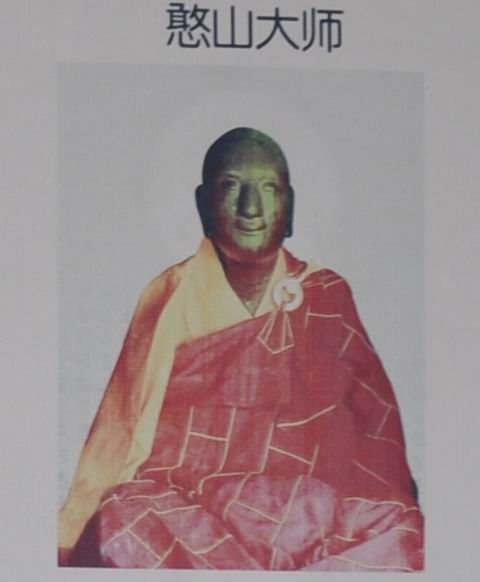

Extracted from the Transmission of the Lamp A ‘Personal’, or ‘mind to mind’ transmission is described as follows. Enlightenment is the realisation of the empty mind ground (relative enlightenment) - and the integration of this realisation of with all phenomena (full enlightenment). An enlightened being (or ‘Bodhisattva’) is neither attached to the void or hindered by phenomena – a reality that ‘deepens’ in maturity as the years go by. Transmission is the recognition by an enlightened master that a disciple has realised this state, and is therefore able (and ‘authorised’) to teach others to realise this state. A ‘Supportive’ transmission, by way of contrast, is designed to ‘assist’ and ‘uplift’ a practitioner in preparation for the achievement of ‘relative’ and ‘full’ enlightenment, and to transition into a ‘Personal’ transmission should an individual achieve a suitable status of realisation. Master Han Shan Deqing [憨山德清] (1545-1623) may be taken as a reliable model of a Ch’an monk who realised full self-enlightenment (confirmed through the guidance found in the Surangama Sutra). Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) inherited the Dharma-Name ‘Deqing’ (德清) - or ‘Virtuous Clarity’. Master Han Shan understood that ‘sound’ was only perceptible through a ‘subject’ - ‘object’ duality when the mind ‘moved’. When the mind was ‘stilled’, all perception came to an end for the realisation of ‘relative’ enlightenment’. From this position, and following a period of further training, Han Shan’s mind appeared to ‘expand’ and embrace the entire environment (full enlightenment) - a luminous state within which the mind becomes like a mirror and reflects all things. Another text designed to assist the self-enlightenment process is the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra – within which the enlightened layman – Vimalakirti - ‘corrects’ the Buddha’s monastic disciples who have only realised the state of ‘relative’ enlightenment. Through his ‘supportive’ presence and influence he provides the outer and inner conditions (and expert stimulus) to ‘assist’ these monks to ‘move beyond’ their own limited achievements. Vimialakirti’s example is the ‘essence’ of the Guild of Hui Neng’s ongoing Cao Dong transmission. ACW (5.10.2020)

‘...After my death, if you carry out my instructions and practise them accordingly, my being away from you will make no difference. On the other hand, if you go against my teaching, no benefit would be obtained, even if I continued to stay here.’

Then he uttered another stanza: “Imperturbable and serene the ideal man practises no virtue. Self-possessed and dispassionate, he commits no sin. Calm and silent, he gives up seeing and hearing. Even and upright his mind abides nowhere.” Having uttered this stanza, he sat reverently until the third watch of the night. Then he said abruptly to his disciples, “I am going now,” and in a sudden passed away. A peculiar fragrance pervaded his room, and a lunar rainbow appeared which seemed to join up earth and sky. The trees in the wood turned white, and birds and beasts cried mournfully. ...The Patriarch inherited the robe when he was 24, had his hair shaved (i.e. was ordained) at 39, and died (sat upright) at the age of 76. For thirty-seven years he preached for the benefit of all sentient beings. Forty-three of his disciples inherited the Dharma, and by his express consent, became his successors; while those who attained enlightenment and thereby got out of the rut of the ordinary man were too numerus to be calculated. The Altar Sutra of Hui Neng (Chapter 10 – His Final Instructions) |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed