|

Buddhist monasticism is flexible. Although it is correct to assume that it is usually necessary for an individual to undergo a period of isolatory training (to establish and stabilise the realisation of the void) - it is also true that compassionate (Bodhisattva) activity must also be pursued throughout the myriad conditions that define worldly existence. This is true of all Buddhist traditions - as even the Bhikkhus of the Theravada School must "walk" (in a self-aware manner) through the surrounding (lay) villages - begging for food on a daily basis. Living a hermitic or cloistered existence is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Of course, this period may be repeated more than once and last any length of time. When entering different situations - the Bodhisattva does not lose sight of the realised void regardless of the external conditions experienced. The Sixth Patriarch (Hui Neng) spent around 15 years living with bandits and barbarians in the hills - retaining a vegetarian diet - even though he was not yet formally ordained in the Sangha. Within China, the Mahayana Bhikshu must take the hundreds of Vinaya Discipline Vows as well as the parallel Bodhisattva Vows (the former requires complete celibacy whilst the latter requires moral discipline but not celibacy). Anyone can be a "Bodhisattva" - whilst a formal Buddhist monastic must adhere to the discipline of the Vinaya Discipline. A lay Buddhist person also adheres to the Vinaya Discipline - but only upholds the first Five, Eight or Ten vows, etc. Vimalakirti is an example of an Enlightened Layperson whose wisdom was complete and superior to those who were still wrapped in robes and sat at the foot of a tree. In the Mahasiddhi stories preserved within the Tanrayana tradition - the realisation of the empty mind ground (or all-embracing void) renders the dichotomy between "ordained" and "laity" redundant. The Chinese-language Vinaya Discipline contains a clause which allows, under certain conditions, for an individual to self-perform an "Emergency" ordination. This is the case if the individual lives in isolation and has no access to the ordained Sangha or any other Buddhist Masters, etc. The idea is that should such expertise become available - then the ordination should be made official. However, the Vinaya Disciple in China states that a member of the ordained Sangha is defined in two-ways: 1) An individual who has taken both the Vinaya and Bodhisattva Vows - and has successfully completed all the required training therein. 2) Anyone who has realised "emptiness". Of course, in China all Buddhists - whether lay or ordained - are members of the (general) Sangha. The (general) Sangha, however, is led by the "ordained" Sangha. As lay-people (men, women, and children) can realise "emptiness" (enlightenment) - such an acommplished individual transitions (regardless of circustance) into the "ordained" Sangha. This is true even if such a person has never taken the Vinaya or Bodhisattva Vows - regardless of their lifestyle or position within society. Such an individual can be given a special permission to wear a robe in their daily lives - but these individuals do not have to agree with this. Realising "emptiness" is the key to this transformative process. Emptiness can be realised during seated meditation, during physical labour (or exercise), or during an enlightened dialogue with a Master. The first level is the "emptiness" realised when the mind is first "stilled". This "emptiness" is limited to just the interior of the head - but the ridge-pole of habitual ignorance has been permanently broken (this is the enlightenment of the Hinayana) - and is accompanied by a sense of tranquillity and bliss. This situstion (sat atop the hundred-foot pole) must be left behind. Through further training, the "bottom drops out the barrel" - and the perception of the mind expands throughout the ten directions. Emptiness embraces the mind, body, the surrounding environment - and all things within it.

0 Comments

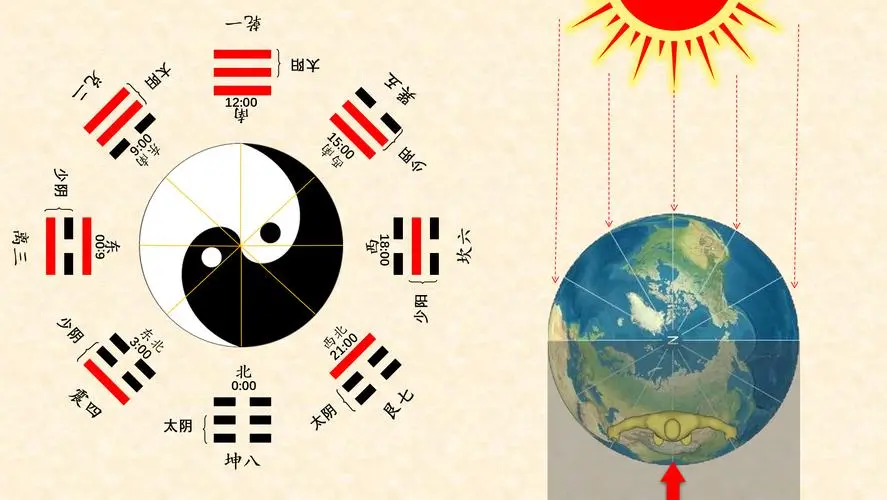

Dear B It is interesting that those who were illiterate - such as Hui Neng - could have the essence of mind development conveyed to them by simply studying the "shape" (form) of the Trigrams and Hexagrams. Of course, Master Cao develops this idea through his shaded roundels. Indeed, it could well be that the roundels of the Caodong School eventually led to the development of the Taiji Tu [太極圖] (Yin-Yang Symbol) that was developed during the latter Song Dynasty. Either way - the "beyond words" teaching - may have had its root in illiteracy - as the historical Buddha could not read or write - as astonishing as that seems!

Richard Hunn stated that the Five Ranks of the Caodong School are very sophisticated and quite often difficult to understand. In essence the Caodong Ch’an Method is a condensing of the teachings found within the Lankavatara Sutra. Without possessing a copy of this Sutra (which Bodhidharma brought to China in 520 CE) – the “Method” can be easily learned, preserved, and transmitted by word of mouth and through awe-inspiring deportment (hence the “odd” behaviour of many Ch’an Masters and their Disciples). Within ancient China, perhaps around only 10% of the population could read or write. Such men (normally not women) were almost always Confucian Scholar-Officials (or their students). It is also true that some Ch’an Masters were also Confucian Scholars – as were Master Dong and Master Cao – who founded the Caodong School of Ch’an (the two names are reversed to express a better rhythm within Chinese-language speech patterns). Both these men understood the “Yijing” (Change Classic or “I Ching”) and were conversant in the Trigram and Hexagram ideology. This is why the Five Ranks are premised upon two Trigrams and three Hexagrams. The internal logic of how these lines “move” from one structure into another - is the underlying reasoning that serves as the foundation for the Caodong School. The minutiae of this doctrine is not the purpose of this essay (as I have published a paper on this elsewhere). Within genuine Caodong lineages it is taught that the Caodong Five Ranks can be taught as “Three” levels of realisation or attainment: 1) Guest (Form) – ordinary deluded mind within which the “Void” is not known. (Rank 1) 2) Host (Void) – the “Void” is known to exist and a method is applied to locate and realise its presence. (Rank 2) 3) Host-in-Host (Void-Form Integration) – the “Void” is fully realised, aligned, and integrated with the “Form”. (Rank 3, 4 & 5) The problem with “lists” is that they are often dry and one-dimensional. What does the above explanation mean in practical reality? The following is how this path is explained from the perspective of experiencer: a) When the mind is looked into – all that is seen - is the swirling chaos of delusion (Form). b) By applying the Hua Tou or Gongan Method – this confusion ceases, and an “empty” mind is attained. However, this “emptiness” is not permanent and must be continuously accessed through seated meditation to experience it more fully. Furthermore, even when stabilised – this experience of “emptiness” is limited only to the inside of the head. This is “Relative” enlightenment that should not be mistaken for “Full” enlightenment. Despite its limitation, nevertheless, such a realised state is far beyond the ordinary. c) When the “empty” mind naturally “expands” it encompass and reflects the physical body and all things within environment (the “Mirror Samadhi”). This is the attainment of “Full” enlightenment - and the realisation of the “turning about” as described in the Lankavatara Sutra. Although no further karma is produced and given that a great amount of past karma has been dissolved, the very presence of a living physical body still attracts karmic debts that may need paying. Further training is required to clear the surface mind of residual “klesa” (delusion) and to purify behavioural responses. Traditionally, the Chinese Ch’an Master refused to speak about the post-enlightenment position.

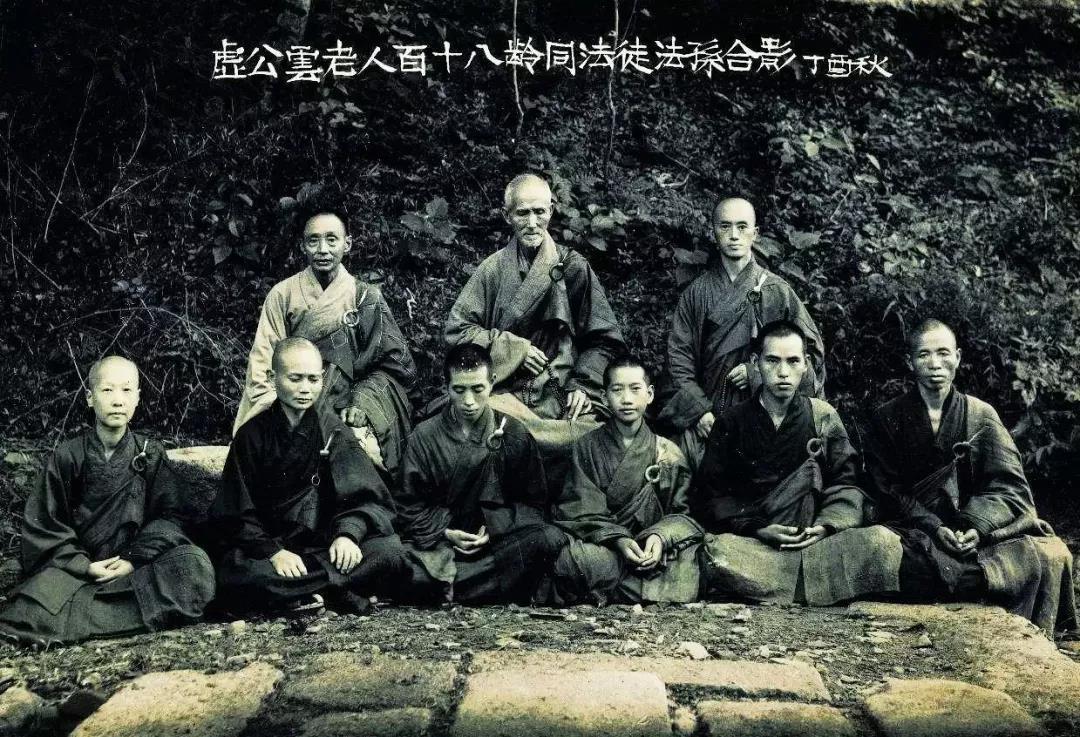

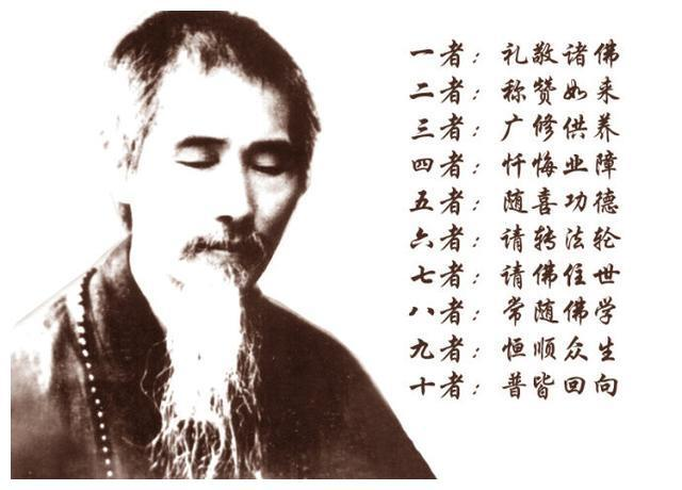

Dear Tony Richard Hunn (1949-2006) was both my academic and spiritual teacher. He taught me how read, write and interpret traditional Chinese ideograms. I trained with him between 1989-2006. He was an English gentleman who could read, write and speak many dialects of the Chinese language - including the rare Hakka dialect spoken by our Chinese grandmother (whom Richard met in 2000 during a visit to our house). I wrote this for Richard following his passing: He helped me understand and balance the two sides to my character - the 'Chinese' and the 'British'. He used to work for Pebble Mill (BBC) - but was an academic expert on the Chinese language and Chinese Buddhism. His spiritual teacher was Charles Luk (1898-1978) - who in-turn trained under the Great Chinese Ch'an Master Xu Yun (1840-1959). To me, Richard Hunn represented everything that is great and good about the UK. In 1991, Richard Hunn gave-up his life in the UK and migrated (via a modest academic study grant) to Kyoto in Japan. He lived there between 1991-2006 (marrying a Japanese woman - Taeko - with whom I am still in communication with today). Why did he choose Japan? Well, he received an academic grant to study the transmission of Chinese Ch'an from China to Japan - which included examining the Chinese Ch'an Temples that still exist in Japan - separate and distinct from the Japanese 'Zen' Temples. Every August-September each year, Richard Hunn (who worked at Kyoto University) used to escort a number of his English Study students (usually 20 or so) to look around London. The students would stay for about two-weeks before returning as a group to Japan without Richard. Being 'free' of this responsibility, Richard would visit all his family - before spending a week or two at our house in Sutton (Priory Road - where you showed me an excellent Tensho Kata in the hall). We would meditate together and discuss reality deep into the night. He used to test my understanding of Chinese ideograms - crushing my stupidity and encouraging my insight. Even so, I was reticent to actually 'translate' anything - until a number of Mainland Chinese students studying in the UK checked my work - and encouraged me to start translating. I was then put in contact with a number of academics in China and my life entered a new phase. Richard Hunn visited a number of old martial arts 'Dojo' positioned in and around the remote Kyoto hills. He was often 'Introduced' with a letter to various Old Masters who lived in rustic huts - usually with only one or two disciples. Many practiced Chinese arts unaltered in anyway for hundreds of years. These Japanese men and women also studied traditional Chinese ideograms - the original language of the arts they preserved. As these arts existed 'outside' the grading (coloured-belt) system of Japan - they were excluded from all State financial support - hence their simplistic existence. Best Wishes Adrian

Dear B As far as I am aware, Master Xu Yun had studied the Yijing as a child (and youth) under the strict supervision of the numerous tutors that his (Scholar-Official) father traversed through the household. This was in preparation for Xu Yun to take the 'Scholar-Official' Government Examination - which required the rote learning of the Four Books and the Five Classics - and the meticulous replication (word for word) of required sections of each text. A good Scholar-Official must demonstrate how he would deal with each real-world incident by referring to a precise and exact extract of whichever divine-text was relevant to the situation. There could be NO deviation from this ancient (and 'perfect') process if a candidate was to be successful. Remember, tens of thousands applied - and only the low-hundreds would be 'Passed' - according to governmental needs (which meant thousands who had 'Passed' would be 'Failed' as no posts existed for them to be allocated toward). On paper (and in public), Master Xu Yun always distanced himself from Confucian and Daoist Texts (the Yijing in China is considered a 'Confucian' Text). This is to be expected from a man who betrayed the will of his father and instead embraced the Path (Dharma) of the Buddha - a religion that even today is considered 'foreign' in China. To be successful on this path - Xu Yun had to completely abandon what appeared to be the worldly path as defined by Chinese convention. Therefore, the (Indian) Vinaya Discipline took the place of the Four Books and the Five Classics. If this was the cae, then why did Xu Yun (privately) advise Charles Luk to study the Yijing and integrate it with the Ch'an Path? In the UK - Richard Hunn (my primary teacher) was considered the most prominent 'Master' of the Yijing - as he could read the original (and ancient) Chinese ideograms and even lectured about this Text to ethnic Chinese students attending University in Great Britain in Putonghua! For our Ch'an (Caodong) Lineage (Master Xu Yun inherited and transmitted all Five Houses of Ch'an - but in his private transmission he only favoured the 'Caodong') - the Yijing is a pivotal and yet 'hidden' Text. Remember, the Caodong Masters were also experts in the study of the Yijing - and they used trigrams and hexagrams to devise the Five Ranks System. Xu Yun was the opinion that it is only through the study of the Yijing that the Caodong methodology can be truly understood. In this regard, John Blofeld was never privy to this advanced knowledge. If he met Xu Yun - it was merely for a few minutes where Blofeld (by his own admission) spouted nonsense. Of Course, I salute your efforts and you must never be afraid (as I know you are not) to pull the whiskers of the tiger! With Metta Adrian

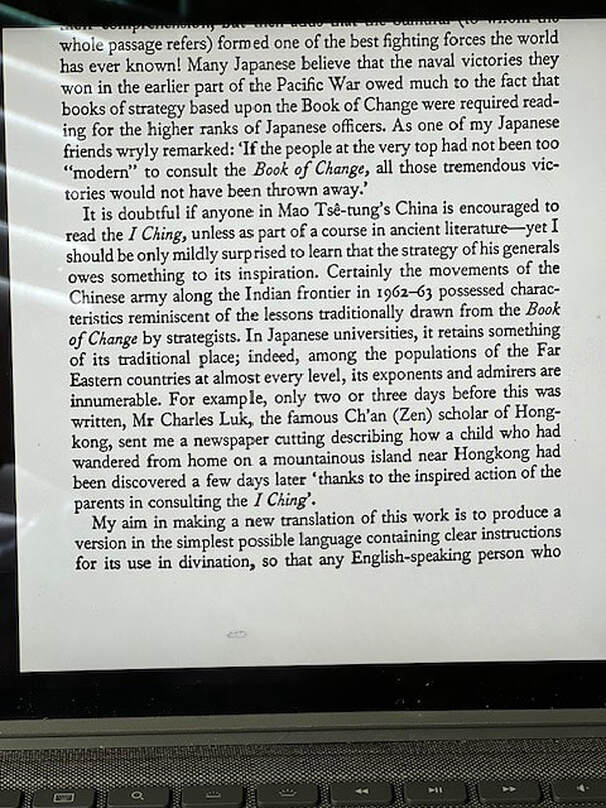

Dear B Douglas Harding used to hold Zen meditation sessions by lying on the floor. He had no time for formal structure - as 'having no head' also apparently meant that 'he had no body' - although most people who encounter his work seem not to realise the latter. Richard Hunn knew John Blofeld and Douglas Harding - although if he knew Terrence Grey - nothing was said to me. Blofeld mentions meeting Xu Yun - but Xu Yun does not mention meeting Blofeld. This need not negate the encounter - as Xu Yun was photographed with numerous Westerners - many of whom are not mentioned in his biography. In the UK - the barbarous treatment meted-out by the Imperial Japanese Army to British POWs and civilians is still remembered with disgust and derision - as is their savage treatment toward tens of millions of Asian victims. Just what Blofeld is talking about does not ring true. Richard told me that Blofeld eventually retired to Thailand - and 'gave-up' Buddhism in the last years of his life - becoming anti-Asian and pro-Christian, so perhaps his wayward attitudes express these changes. I inherited Charles Luk's papers, and having looked through the volumes, I can say that there is no mention of John Blofeld, Douglas Harding or Terrence Grey. Charles Luk was opposed to Japanese religious corruption and actively campaigned against it. He certainly would not have assisted Blofeld if he knew of his pro-Japanese attitudes. As to hilly Hong Kong mountains - he is probably speaking of the Sai Kung area of the New Territories - where our Ancestrial village used to be. As the area is now a 'National Park' - the US social media has extended the so-called '411' mythology to include this area. Whenever I visited the area - I used to make sure I was with Chinese relatives who knew where they were going. Yes - Richard Hunn gave me his copy of John Blofeld's Yijing. It is a peperback to which Richard added a stouter cover. Of course, it is not the full Yijing, but only the Hexagrams, its line commentaries, the Judgements and Images. From what I can see, I believe Blofeld is copying Wilhelm and is not working from the original Chinese language text. It is a re-interpretation of a translation. Of course, I suspect there are hundreds of these re-interprtations in the English language by now - and that a certain selection can grant an overview of the original text. I am told that an astonishing 600,000 Americans go missing each year in well sign-posted National Parks and National Forests - although all but 6,000 are found safe and well - and that this finding is through the application of the scientific method. When people's lives are at stake I doubt superstition can replace logic and reason. In the days that Blofeld is referring to - the New Territories were strewn with hundreds of villages - many of them Hakka (he does not know this because he never went there). The distance between villages was quite often miniscule. I would say that getting truly lost would have been very difficult as there were settlements everywhere. These are the settlements the Imperial Japanese Army raped and pillaged their way through - killing at least 10,000 people in a relatively small area (1941-1945). The Yijing certainly did not assist the ethnic Chinese escape this fate. One last point that Blofeld is missing is that the Imperial Japanese Government 'banned' everything 'Chinese' - and this included the study of the Yijing. Blofeld is, therefore, misinformed and I would say, not to be trusted. With Metta Adrian

Richard Hunn (1949-2006) passed away 17-years ago (as of October 1st, 2023). He was just 57-years old - having suffered from a short but devastating illness (Pancreatic Cancer). As with any good Ch'an Master - Rixhard Hunn tended to refuse any formal titles or awards - as he felt such baubles weighed-down a practitioner diverting the awareness away from the 'host' and toward the 'guest'! Besides, Charles Luk bestowed upon him the Dharma-Name of 'Wen Shu' - the name of the Bodhisattva Manjushri who appears all the way throughout the Buddhist Sutras - spreading his 'wisdom' and 'compassion' to all and sundry! After emigrating to Japan in 1991, Richard Hunn decided to carry-out a pilgrimage to Mount Fuji! For reasons only known to himself - this journey was carried-out in the depths of Winter - when the wind blew and the snow fell! When things were looking bleak - a person appeared out of nowhere and helped Richard Hunn seek-out assistance! A passing Senior Police Officer decided to take Richard into Custody whilst he investigated his background and motives. He was surprised when Richard started to converse with him in the Japanese language. When the Officer had sat and discussed Zen for an hour in a comfortable Police Station (whilst Richard was given a warm meal and drink) - The Officer ordered that Richard be driven to the peak of Mount Fuji and given a hotel room usually reserved for the Police! This was apparently out of respect for Richard's understanding of Zen - and his mastery of the Japanese language! Interestingly, around 2002 Richard visited my family home in Sutton (South London). I eventually introduced him to my Hakka Chinese grandmother - and to my astonishment he started talking to her in the Hakka language! She was taken by as much surprise as was I! Apparently, he had known a number of Hakka Chinese people at Essex University (I believe from Malaysia) who were members of the University's Chinese Buddhist Association. This ethnic Chinese group actually voted Richard to be the 'President' - the only non-Chinese person to have held that post up to that point! I believe this was during the late 1970s - when he also participated in the Multicultural Department of BBC's Pebble Mill (a general education and entertainment programme). Richard often arranged for British Buddhist content to be filmed and broadcast. He was personally responsible for a documentary covering the Thai Buddhist Temple (Buddhapadipa) situated in Wimbledon! Richard Hunn had spent an extended time sat meditating in that temple - with the Thai Head Monk suggesting that he became a Theravada Buddhist monastic! I watched this programme as a child - and only many years later would I meet Richard Hunn - and eventually take my place in the Meditation Hall of Buddhapadipa! Charles Luk had said that the empty mind ground underlies ALL circumstances an that it does not matter where we train just as long as we effectively 'look within' with a proper intensity and direction! Whilst Richard Hunn was establishing himself in Japan - he suggested that I travel to a Theravada country and train 'at the source', so-to-speak. This is how I ended-up training under Mangala Thero (in 1996) at the Ganga Ramaya Temple (in Beruwela) - situated in Sri Lanka. I have subsequently discovered that Mangala Mahathero has passed away after spending the last decade of his life living and meditating in isolation. I am told that Richard Hunn would sit 'still' for hours on end in various Zen Temples throughout the Kyoto area. Although outwardly he was practicing 'Zen' - inwardly he was practicing 'Caodong' Ch'an - the preferred lineage of Master Xu Yun (1840-1959). Although none of us know how long we will be on this Earth - we must remain vigilant and use our time effectively and productively! Not a single second must be wasted when it comes to self-cultivation! Instead of reading this board - look within! At this time of year I usually contact Richard's widow - Taeko - and offer my respects!

Chinese Ch'an is the method of permanently altering one's perception. This is achieved by changing 'how' and 'where' the individual places their 'attention'. The default setting for human-beings - which is linked to the evolutionary drive to survive - requires the general attention to be fixed upon the sensing of permanent (external) stimuli - as mediated through the six sense-organs. Modern science, of course, informs us that there are many more than just the assumed 'five' senses in the West (perhaps as many as 'thirty') - but these further senses are in fact specific aspects (or elements) of perception - and easily fall within the Buddha's schematic of defining the 'mind' as a 'sense'. Human ancestors had to be acutely 'aware' of their surroundings if their chances of survival were to be enhanced. After the development of the human mind, body and environment - settled human culture allowed individuals to contemplate their existence. As much of this is speculative in nature - it falls under the subject of religion and spirituality - with the modern trend involving secularised conspiracy theories. The point is that there are many 'external' places (the 'guest' position) where individuals are able to place their awareness. It does not matter what belief system sustains this 'externality' - as the 'guest' position is NEVER left. The Chinese Ch'an tradition offers a methodology to alter, shift and change this orientation. Chinese Ch'an does this by transitioning the default setting of human perception away from the 'guest' position - and toward the 'host' position. The 'host' position is comprised of the empty essence that underlies ALL perception. Therefore, it does not matter where an individual lives, when an individual lived - or the culture that defines the prevailing material conditions - the empty mind ground will ALWAYS underlie whatever physical structures the conditioned elements construct. Today, many spiritual schools are content to pursue a material path that encourages adherents to become attached to this or that outward manifestation - often for a large fee! Being 'attached' to whatever form of externality that takes your attention is not difficult and you certainly do not need another's permission or guidance to attain it. This is why a genuine Ch'an teacher is often unpopular in the world of material externality - as he or she continuously speaks and acts from the 'host' position. The genuine Ch'an teacher is a beacon of stable hope in a sea of changing uncertainty - as was the example of Master Xu Yun (1840-1959). In the meantime, words, silence, actions, and inactions - all serve to turn the adherent's attention BACK (inward) toward the empty essence of ALL material experience. If you are looking for the confirmation of your existing views and opinions (the 'guest') - then you have come to the wrong place. There are many 'businesses' out there that will sell you a robe and an ordination certificate. How's that for unpopularity?

Although eulogised more or less the world over today – Master Xu Yun attracted his fair share of criticism. Although completely indifferent to worldly affairs he was accused of being a ‘rightest’ and a ‘leftist’ at different times in his existence. Those jealous of his spiritual power (and seniority) within the Chinese Buddhist System – accused Master Xu Yun of breaking the very Vinaya Discipline he fervently enforced upon his disciples. Quite often this involved the rules surrounding sexual self-control and celibacy – with Master Xu Yun accused of participating in relations with male acolytes. Of course, there was never any material evidence to substantiate these rumours. At one time a young woman took her clothes-off in front of a meditating Master Xu Yun on a boat packed with witnesses – and he never reacted. It is speculated that this woman was paid to do this in an attempt to secure material evidence regarding Master Xu Yun breaking the Vinaya Discipline.

Part of the reason inspiring these baseless attacks involved the Imperial Japanese presence in China between 1931-1945 – which saw an attempt at manipulating the Chinese Sangha into adopting the Japanese Zen practice of NOT following the Vinaya Discipline and allowing Buddhist ‘monks’ to be married, eat meat and drink alcohol. There were some collaborative elements within a rapidly modernising Chinese culture that viewed Master Xu Yun’s attitude as being old fashioned and behind the times. Master Xu Yun, despite this pressure from without and within Chinese culture, nevertheless, refused to buckle and instead reacted with an ever-greater vigour in calling for the upholding of the Vinaya Discipline! When told what others were negatively saying about him, Master Xu Yun would laugh and brush the insult aside. What others said was viewed by Master Xu Yun as being a product of greed, hatred, and delusion – and the very ignorance that following of the Vinaya Discipline sought to uproot and dissolve into the three-dimensional emptiness of the empty mind-ground. Just as following the Vinaya Discipline represented the pure ‘host’ position – the impure ‘guest’ position represented the dirtiness of the ordinary, mundane world and its machinations. Why follow the latter when the former offered safety, sanctuary, and a relief from human suffering? Pretending to be a ‘monk’ when immersed in the filth of the ‘guest’ position of lay-existence is NOT correctly following the Buddha-Dharma as taught by Master Xu Yun. Master Xu Yun shuffled-off his mortal coil 64-years ago (in 1959) – on October 13th (when the Chinese Lunar Callender is converted into the Western Solar equivalent). He was in his 120th-year and had lived nearly two of the 60-years cycles that define the Chinese Zodiac. Although born in the Year of the Rat – and obviously a survivor – Master Xu Yun had no patience for superstition. Indeed, his biography is strewn with accidents, injuries, and the occasional monastic disciplining (involving corporal punishment). None of this bothered him psychologically (as he was ‘detached’ from his feelings) – even if the experience damaged him physically. The question is - how many Buddhist practitioners today are prepared to be like this? All the Tang and Song Dynasty Ch’an Records pursue exactly the same task of clarifying the ‘host’ and defining the ‘guest’. The realisation of the ‘host’ is preferred – whilst the denying of the ‘guest’ is encouraged. Even so – it is clear that even within Chinese-language sources – the mistaking of one for the other is a continuous hazard. If this is true of Chinese culture – how much more difficult must it be for followers of the Dharma in the West? The Ch’an path may be direct – but this fact does NOT make it ‘easy’. Sometimes it is more convenient for individuals to follow simpler paths – even if these paths are harder – and infinitely less likely to achieve results! Ch’an is NOT like this. As Master Xu Yun aged – his body changed dramatically. This is a reality we all face and are facing – and yet despite these profound shifts in physical existence – it is never viewed within the Ch’an tradition as anything more than changes occurring in the ‘guest’ - as the ‘host’ (which must NEVER be departed from) does NOT change one iota regardless of what happens to the physical body or the environment within which it exists. This definition of reality and priority differs significantly from what mainstream society finds interesting or important. This is the entire purpose of the Buddha-Dharma and why the Ch’an Method exists. Sometimes, Master Xu Yun could NOT stand-up due to his very advanced age. This is why he is photographed sat on a chair. He did unduly NOT care about this situation as the ‘host’ position never varies – whilst the ever-changing ‘guest’ position find its place within the accommodating (and three-dimensional) emptiness. This is the eternal lesson that Master Xu Yun teaches humanity. This is the ‘host-in-host’ (that is the integration of the ‘host’ and the ‘guest’) position which transforms the ‘guest’ so that it is correctly viewed as traversing the surface of the mind - whilst remaining entirely ‘empty’ from start to finish! What about the dishonest, the the lying and the deceptive? What happens when such people 'pretend' to seek Ch'an instruction, guidance or clarification? Generally speaking, this is not a problem. If the Ch'an Teacher, Master or Guide has realised the (enlightened) 'host' position, that is the 'empty mind ground', then the questioner - regardless of their apparent 'honesty' or 'dishonesty' - simply represent the (deluded) 'guest' position, and no further explanation is required. The 'honesty' and/or 'dishonesty' of the enquirer means absolutely nothing as the moral-tone of the words such individuals use are all subject (without exception) to being 'returned' to their essential source. The Hua Tou method does not discriminate or support any form of dualistic thinking or acting. The 'enlightening' function is performed by all genuine Ch'an Masters automatically turn ALL words, regardless of the moral orientation of the enquirer, back to their empty essence. When the enquirer is subjected to this process in an appropriate manner, then all delusive constructs 'drop-away' never to arise again. The genuine Ch'an Master is indifferent and can laugh, smile, remain silent or chastise as the need arises. What matters is the realisation that there is NO action the 'guest' can take which will disrupt the 'host'! When the 'host' rests in the 'host' - the trivialities of the 'guest' have NO place to abide or function! Therefore, those who approach - 'approach' - and when 'struck-down' - they 'leave'. Nothing changes in the reflection and there is NO undue movement in the situation.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed